Even most intricate prompts won't earn you copyright on AI content, US officials warn

Key Points

- The U.S. Copyright Office has published guidelines on the eligibility of AI-generated content for copyright protection, emphasizing the importance of human creative contribution.

- Merely providing prompts to an AI system is insufficient to be considered an author, as the AI interprets and executes the prompts autonomously, likened by the copyright office to "rolling a dice."

- To be eligible for copyright, substantial human creativity must be involved, such as making significant modifications to the AI-generated content or creatively curating and organizing elements produced by the AI.

The U.S. Copyright Office released guidelines about when you can copyright AI-generated content. Simply hitting the generate button won't cut it, and each case will still require individual review.

The office is trying to draw a clear distinction between using AI as a creative tool (which is fine) and letting AI completely replace human creativity (which isn't). While getting help from AI tools won't automatically disqualify your work from copyright protection, any system where the AI is making the key creative decisions will face much closer scrutiny.

For AI-created content to qualify for protection, the office says people must add substantial creative elements, actively modify the work, or make creative choices in selecting content. This stance comes from the Copyright Clause of the US Constitution and how courts have interpreted it. The Supreme Court previously established that a work's author must be the person who turns an idea into something tangible.

The prompt problem

The Copyright Office has some bad news for prompt engineers: no matter how creative your prompts are, they don't make you the "author" of AI-generated content.

Their reasoning is pretty straightforward - prompts are just instructions expressing ideas, and copyright law doesn't protect ideas alone. This holds true even for incredibly detailed prompts, since users can't control how the AI interprets these instructions during generation.

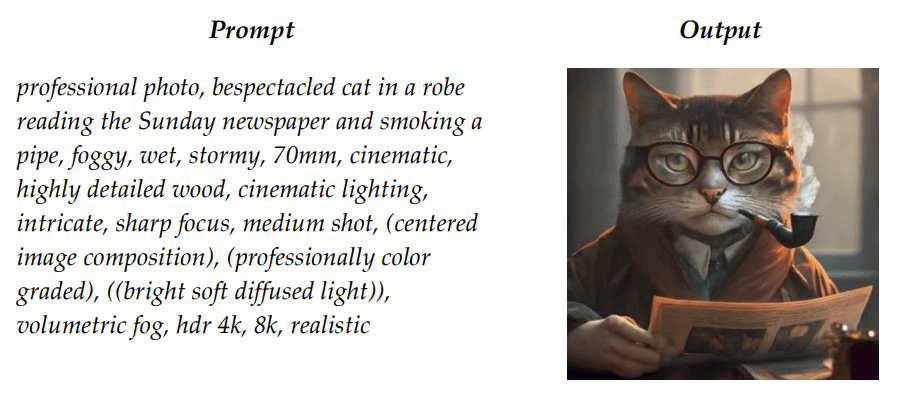

To prove their point, the office ran their own experiment. They fed an AI a detailed prompt: "Create a professional shot of a cat with a headset reading a newspaper and smoking a pipe." The results showed how little control users have over the final output.

The AI did include some requested elements - yes, there was a cat, and yes, it had a headset and pipe. But it completely ignored other specified details and made up new ones on its own. Nothing in the prompt mentioned what breed the cat should be or suggested it should wear a fancy robe, yet there those elements were in the final image.

You might think "well, I'll just keep revising my prompts until I get exactly what I want." But the office says this misses the point. They compare it to rolling dice - you can roll again and again, but you're not controlling how the dice land. And copyright law cares about creative control, not how much effort you put in.

The office also points out that identical prompts often produce entirely different results. This reveals AI as a "black box" that processes our instructions according to its own mysterious criteria, not ours. In other words, the AI is still making the key creative decisions, not the person writing the prompts.

When humans get involved

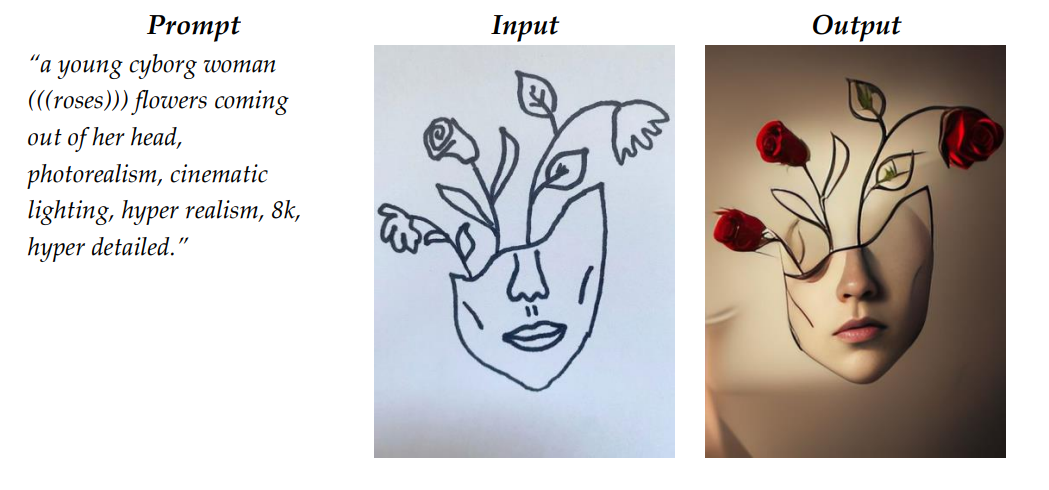

Things get more interesting when people use their own copyrighted work as AI input, and you can still recognize it in the output. The Copyright Office says you keep the rights to your original contribution - it's treated like any other derivative work.

If you creatively select and arrange a mix of human-made and AI-generated elements, that arrangement itself might qualify for copyright protection - even if the AI bits alone wouldn't. This includes using built-in editing tools that come with AI systems. The Copyright Office says whether these changes meet the minimum originality standard (set by the Feist case) depends on the specific situation.

And here's some good news for creators: dropping AI elements into a larger human-created work doesn't mess up its copyright status. A movie keeps its copyright protection even if it uses AI-generated special effects or background art.

While those AI elements themselves aren't protected, they don't affect the copyright status of the whole project. It's not about whether AI was involved, but whether humans made meaningful creative choices along the way.

Following the pattern

The new guidelines are in line with previous decisions. In August 2023, US District Judge Beryl A. Howell rejected an interesting case: AI inventor Stephen Thaler tried to get copyright protection for an entirely AI-generated image. That didn't fly, especially since Thaler insisted the AI itself should be listed as the author.

In another case, the Copyright Office did grant partial copyright to a ChatGPT-written book - but only for how the human author arranged the AI text, not for the actual words the AI produced.

Ed Newton-Rex, former VP Audio at Stability AI, who left the company for ethical reasons, praised the balanced decision. "It's impressive that the US Copyright Office was able to come up with guidance on AI output copyrightability that both AI artists and anti-AI artists are framing as a win."

What the Copyright Office seems to be doing here is threading a careful needle: keeping "authorship" as something fundamentally human while still making room for AI-assisted works when there's real human creativity involved.

The exact boundaries will likely continue to be debated, especially for longer texts - how much human editing is enough to merit copyright protection? It's likely that the Office will have to deal with many more cases, one by one, before artists can feel confident about what they can and cannot copyright in their daily work.

AI News Without the Hype – Curated by Humans

As a THE DECODER subscriber, you get ad-free reading, our weekly AI newsletter, the exclusive "AI Radar" Frontier Report 6× per year, access to comments, and our complete archive.

Subscribe now