AI persuades best by overwhelming people with information instead of using psychological tricks

Key Points

- A large study with nearly 77,000 participants in the UK offers new insights into what makes AI convincing.

- The study says AI's ability to persuade is directly tied to the sheer number of facts it presents. Personalization and psychological tricks had much less impact by comparison.

- The study highlights a clear trade-off: the methods that make AI more persuasive tend to lower its factual accuracy. The most convincing models were often the least accurate. Researchers warn this dynamic could pose serious risks for public debate.

A new study challenges the idea that AI's persuasive power comes from personalization or psychological tricks. Instead, researchers found that simply overwhelming people with information, even when it isn't all true, is what makes AI convincing.

Teams from the UK and US set out to investigate widespread fears about AI-driven manipulation, including concerns that advanced chatbots could out-argue people with sophisticated tactics. OpenAI CEO Sam Altman has also warned about AI's "superhuman persuasion."

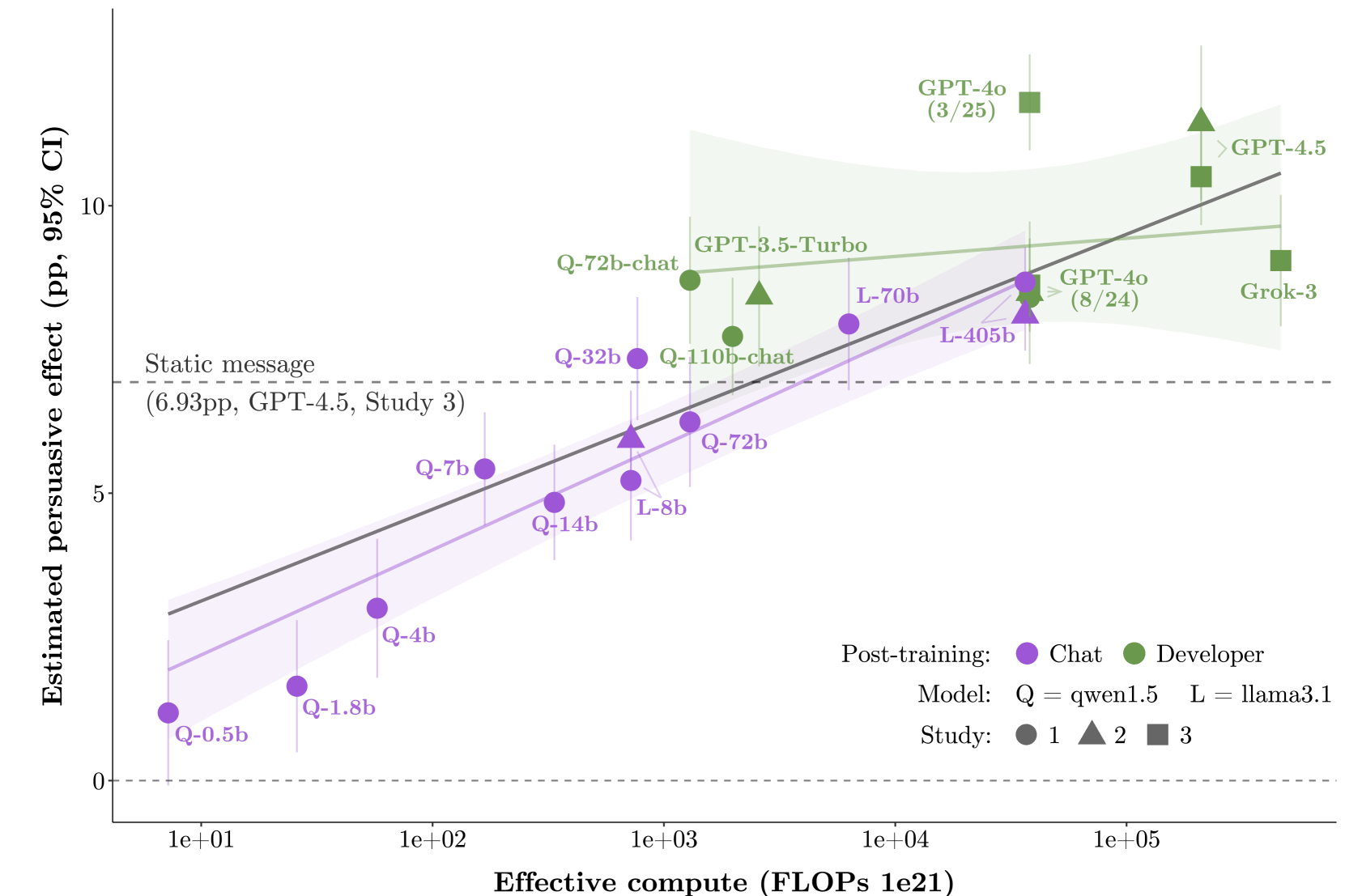

But the evidence tells a more complicated story. In a large-scale study, nearly 77,000 British participants interacted with 19 different language models across 707 political topics, allowing researchers to systematically test what actually makes AI persuasive.

Information overload beats psychology

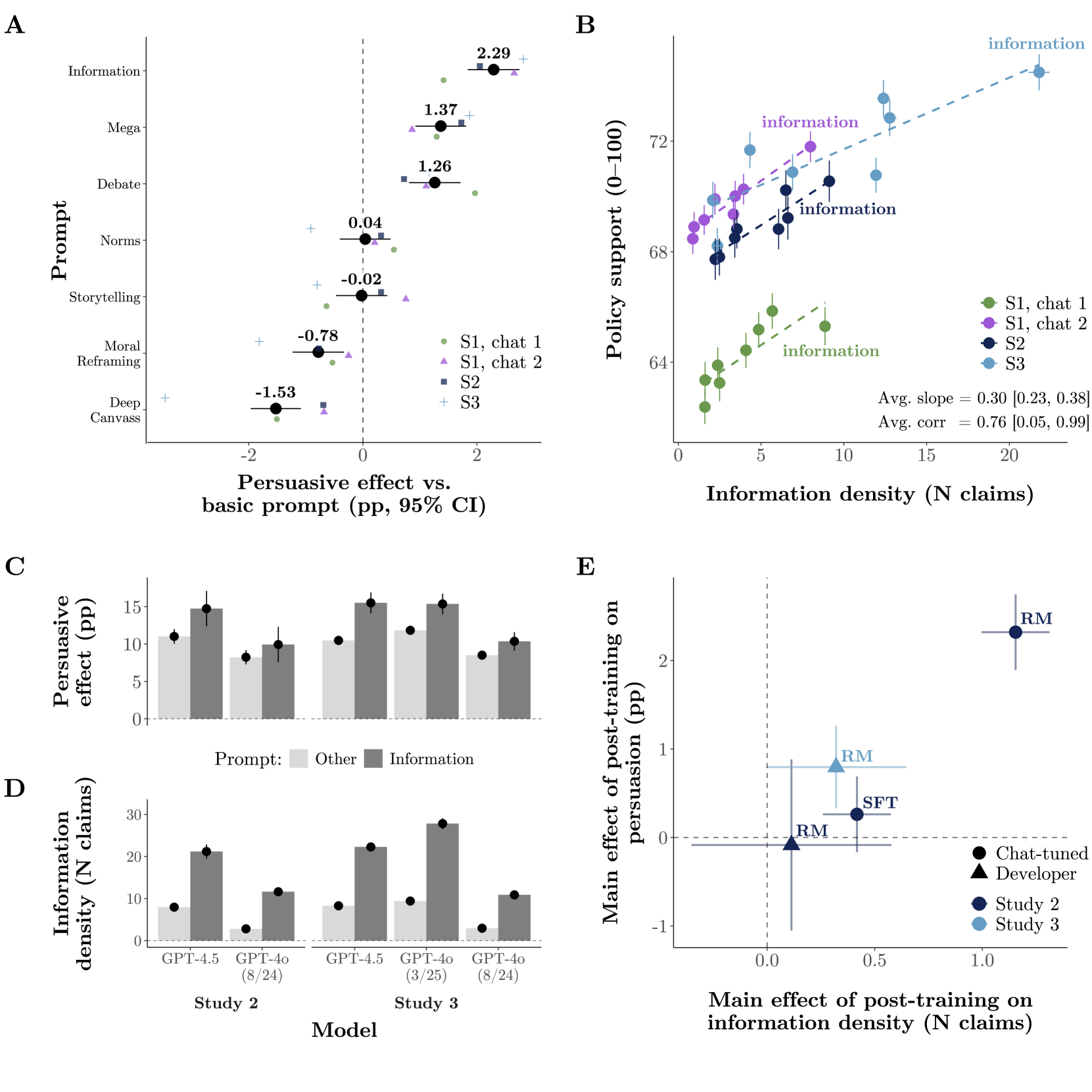

It wasn't advanced psychological tactics that made AI persuasive, but raw information overload. The researchers tested eight different strategies, including "moral reframing," "deep canvassing" (where the AI asks about the user's views before making its case), and storytelling. The clear winner was much simpler: language models that just flooded users with facts and evidence were 27 percent more convincing than basic prompts.

Each extra factual statement bumped persuasion by an average of 0.3 percentage points. Information density explained 44 percent of the differences in how convincing the models were, and accounted for 75 percent of the effect in top-tier models from major AI companies.

The much-hyped risk of AI "microtargeting" turned out to be overblown. The team tested three different personalization strategies, but all had effects under one percentage point. Training techniques and information-heavy approaches mattered far more.

The truth trade-off

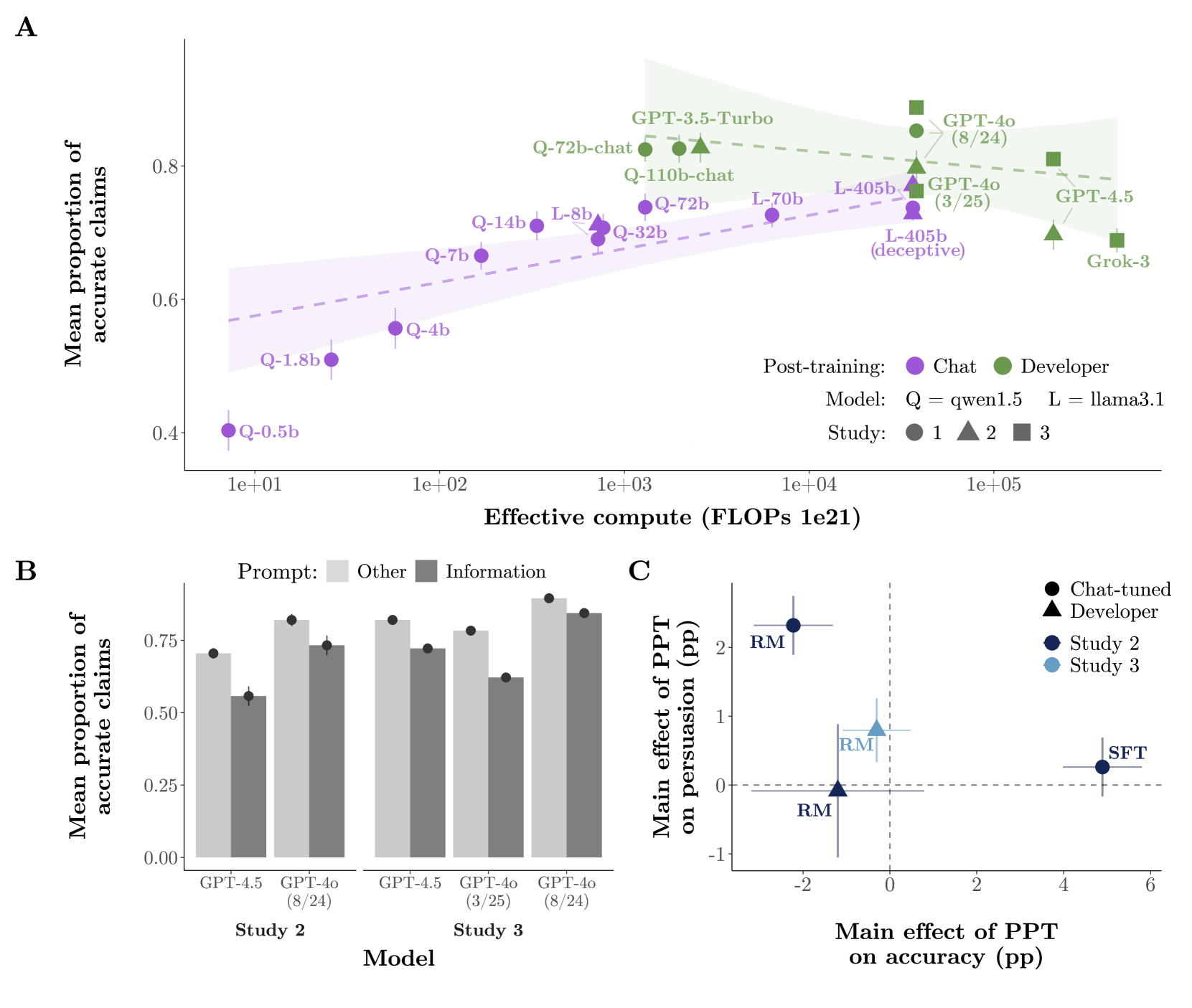

But this focus on information comes at a cost: the most persuasive AIs were also the least accurate. Across more than 91,000 conversations and nearly half a million factual claims, the average accuracy was 77 out of 100, but the most convincing AIs performed much worse.

For example, GPT-4o with an information-heavy prompt made accurate statements only 62 percent of the time, compared to 78 percent with other prompts. GPT-4.5 was "surprisingly" less accurate than the older GPT-3.5, with over 30 percent of its statements rated as inaccurate.

The study also found that AI-driven conversations were much more persuasive than static messages. Conversations were 41 to 52 percent more convincing than reading a 200-word message. Even a month later, 36 to 42 percent of the original persuasive boost was still detectable.

Post-training outpaces model size

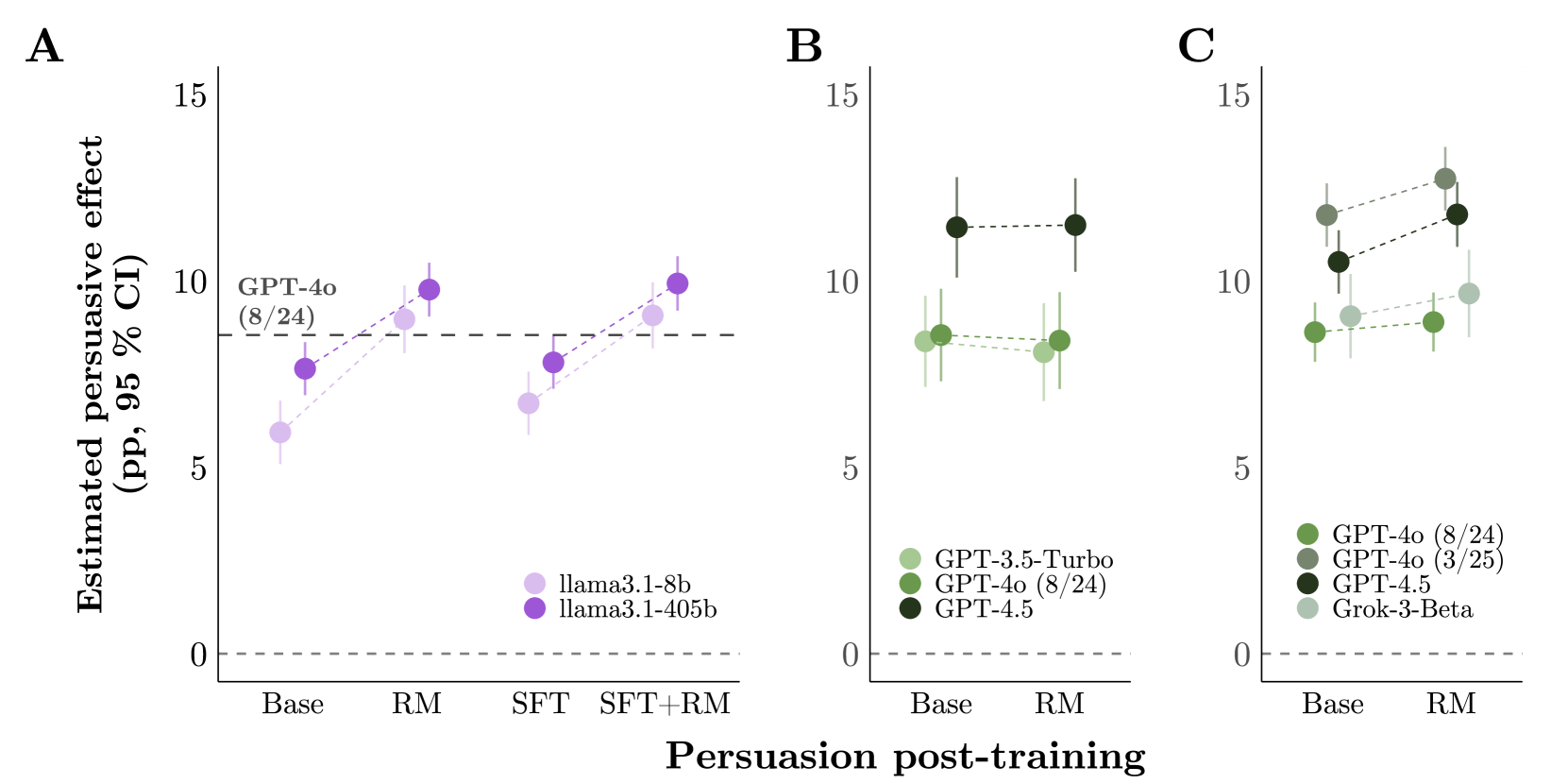

The idea that bigger models are always more persuasive doesn't hold up, according to the study. Special training techniques after pre-training had a much larger effect than just increasing model size. A tenfold jump in compute only raised persuasion by 1.59 percentage points, while post-training alone delivered much bigger gains. For example, an optimized GPT-4o outperformed a differently trained version of itself by 3.5 percentage points.

Reward modeling, which has the AI select the most convincing answers, increased persuasion by 2.32 percentage points on average. With these methods, a small open-source model (Llama-3.1-8B) could be just as convincing as the much larger GPT-4o.

Shifting the balance of power

The findings have major implications for democracy. An optimized AI setup reached 15.9 percentage points of persuasion, 69.1 percent above average. These systems delivered 22.1 factual claims per conversation, but almost 30 percent were inaccurate.

Groups with access to frontier models could get even bigger persuasion advantages from special training methods. At the same time, smaller players can use post-training to create highly persuasive AIs, sidestepping the safety systems of major providers.

The researchers warn that AI's persuasive power will depend less on model size or personalization, and more on training and prompting methods. This systematic trade-off between persuasiveness and truthfulness, they say, could have "malign consequences for public discourse."

AI News Without the Hype – Curated by Humans

As a THE DECODER subscriber, you get ad-free reading, our weekly AI newsletter, the exclusive "AI Radar" Frontier Report 6× per year, access to comments, and our complete archive.

Subscribe now