New benchmark shows LLMs still can't do real scientific research

Getting top marks on exams doesn't automatically make you a good researcher. A new study shows this academic truism applies to large language models too.

AI as a research accelerator represents one of the AI industry's biggest hopes. If generative AI models can speed up science or even drive new discoveries, the benefits for humanity—and the potential profits—would be enormous. OpenAI aims to ship an autonomous research assistant capable of exactly that by 2028.

A new study by an international team of more than 30 researchers from Cornell, MIT, Stanford, Cambridge, and other institutions shows there's still a long way to go. The first authors include the Chinese company Deep Principle, which focuses on using AI in science.

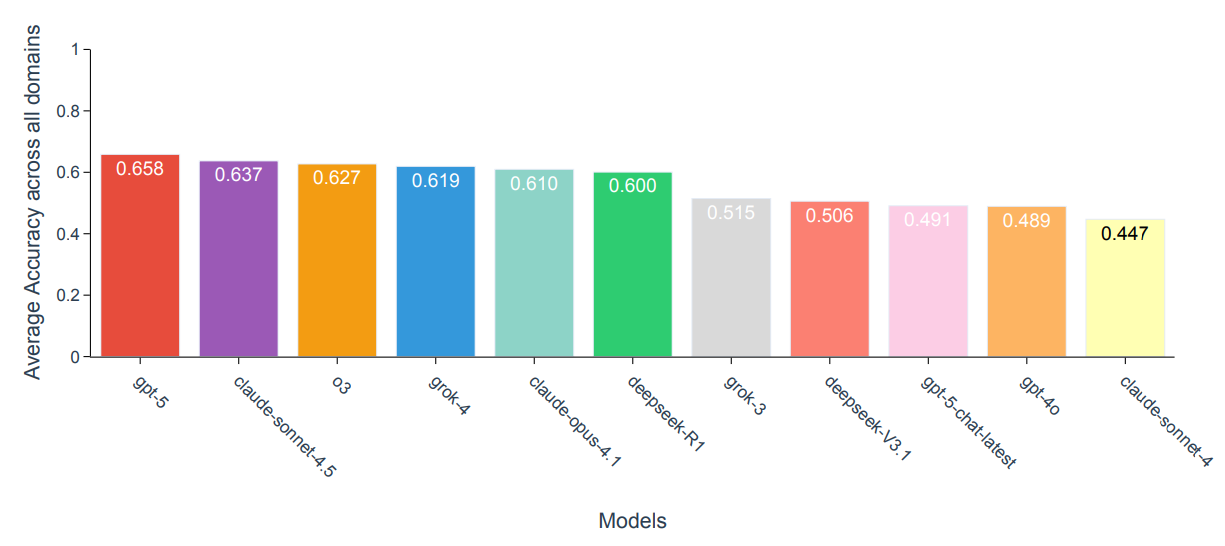

The impressive results on established scientific benchmarks like GPQA or MMMU don't translate well to scenario-based research tasks. While GPT-5 hits 0.86 accuracy on the GPQA-Diamond benchmark, it only manages between 0.60 and 0.75 on the new Scientific Discovery Evaluation (SDE) benchmark, depending on the field.

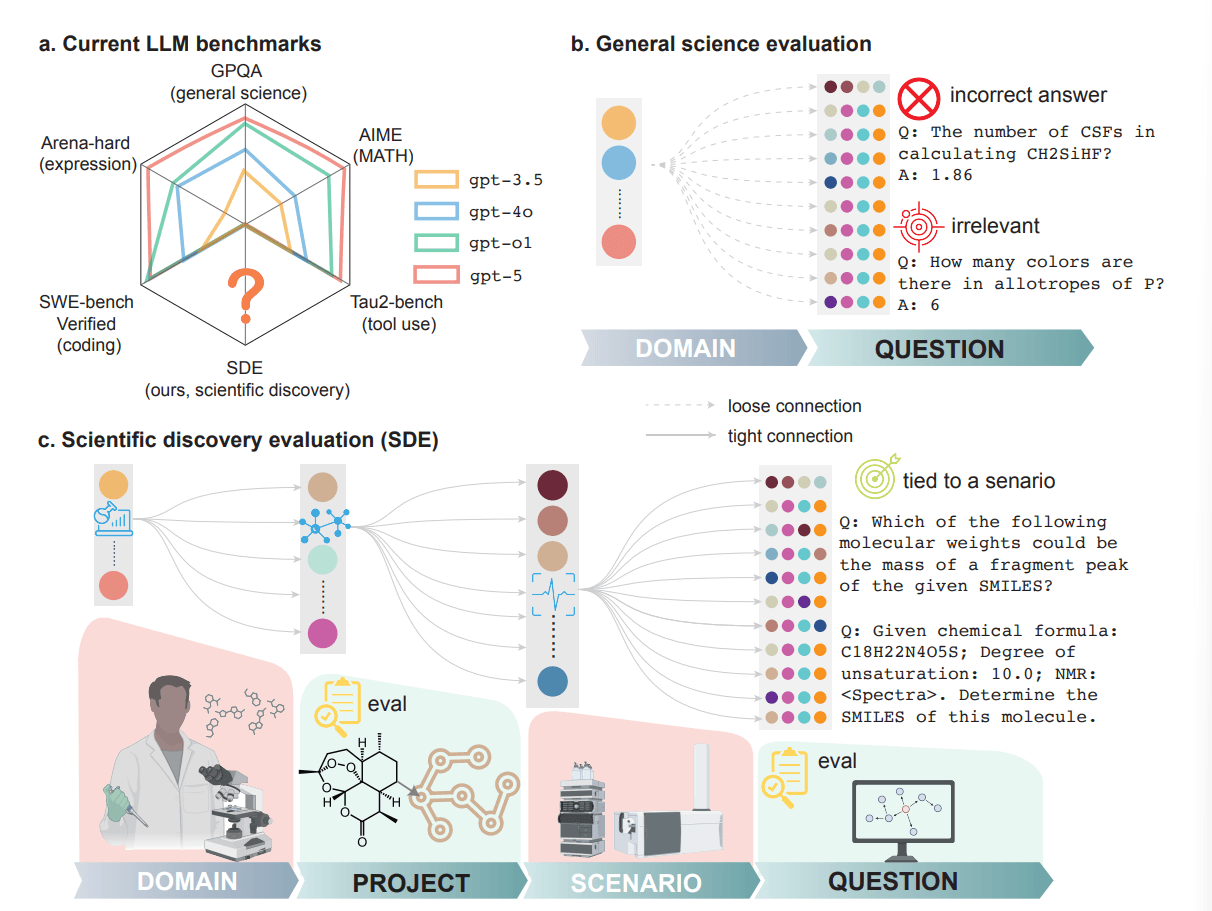

The researchers trace this performance gap to a fundamental disconnect between decontextualized quiz questions and real scientific discovery. Actual research requires problem-based contextual understanding, iterative hypothesis generation, and interpreting incomplete evidence, skills that standard benchmarks don't measure.

Current benchmarks test the wrong skills

The problem, according to the researchers, lies in how existing science benchmarks like GPQA, MMMU, or ScienceQA are designed. They test isolated factual knowledge loosely connected to specific research areas. But scientific discovery works differently. It requires iterative thinking, formulating and refining hypotheses, and interpreting incomplete observations.

To address this gap, the team developed the SDE benchmark with 1,125 questions across 43 research scenarios in four domains: biology, chemistry, materials science, and physics. The key difference from existing tests is that each question ties to a specific research scenario drawn from actual research projects. Expert teams first defined realistic research scenarios from their own work, then developed questions that colleagues reviewed.

The scenarios range from predicting chemical reactions and structure elucidation using NMR spectra to identifying causal genes in genome-wide association studies. This range aims to reflect what scientists actually need in their research.

Performance varies wildly across scenarios

The results show a general drop in performance compared to conventional benchmarks, plus extreme variation between different research scenarios. GPT-5 scores 0.85 in retrosynthesis planning but just 0.23 in NMR-based structure elucidation. This variance holds across all tested models.

For the researchers, this means benchmarks that only categorize questions by subject area aren't enough. Scientific discovery often fails at the weakest link in the chain. The SDE benchmark is designed to highlight language model strengths and weaknesses in specific research scenarios.

Scaling and reasoning hit diminishing returns

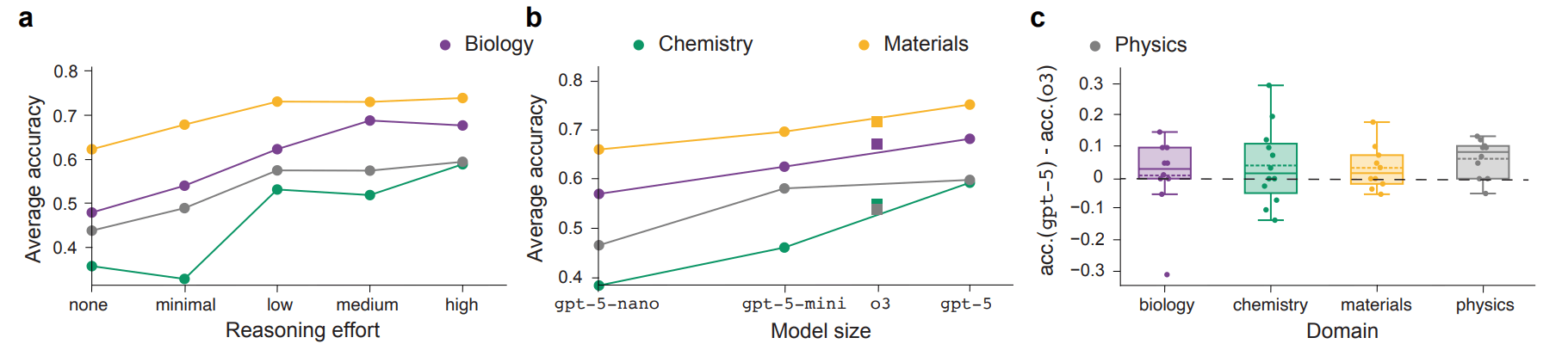

The study also tested whether the usual performance-boosting strategies—larger models and more compute time for reasoning—help with scientific discovery. The answer is mixed.

Reasoning does improve performance overall: Deepseek-R1 outperforms Deepseek-V3.1 in most scenarios, even though both share the same base model. When assessing Lipinski's rule of five, a rule of thumb for predicting oral bioavailability of drugs, reasoning boosts accuracy from 0.65 to 1.00.

But the researchers also found diminishing returns. For GPT-5, cranking reasoning effort from "medium" to "high" barely helps. The jump from o3 to GPT-5 shows only marginal progress too, with GPT-5 actually performing worse in eight scenarios.

The takeaway: the current strategy of increasing model size and test-time compute, which recently drove major progress in coding and math, is hitting its limits in scientific discovery.

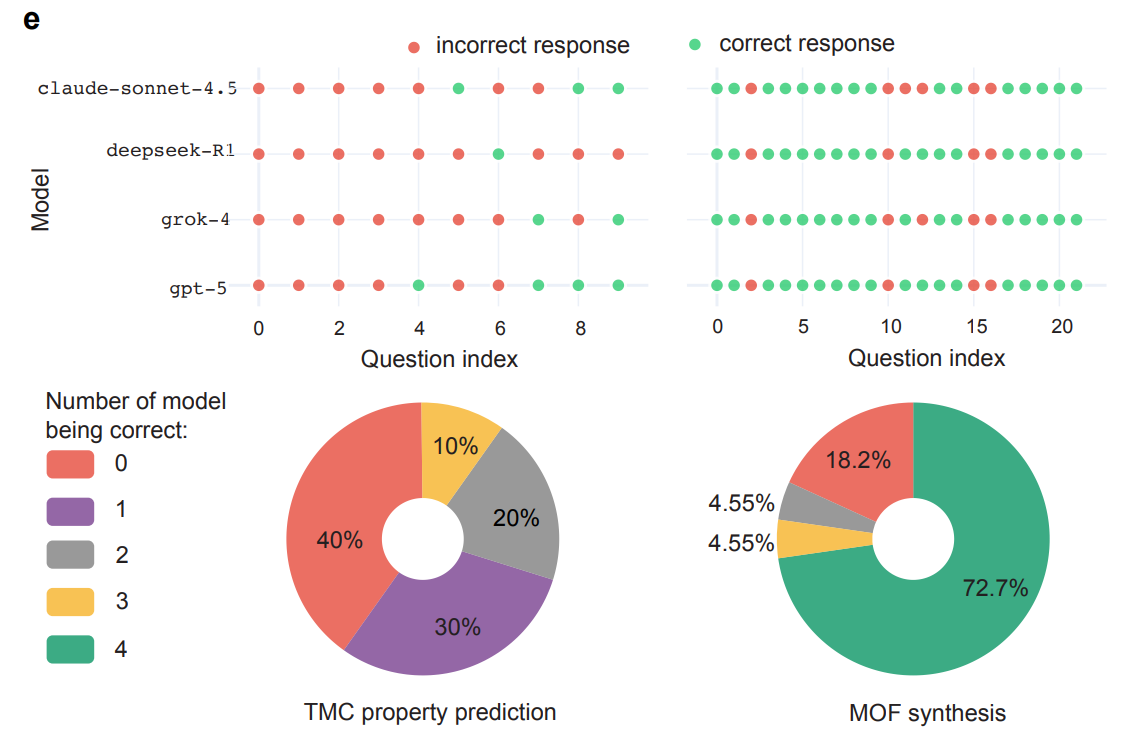

Top models fail in the same ways

Another finding: the best models from different providers, GPT-5, Grok-4, Deepseek-R1, and Claude-Sonnet-4.5, show highly correlated error profiles. In chemistry and physics, correlation coefficients between all model pairs exceed 0.8. The models often converge on the same wrong answers, especially for the hardest questions.

The researchers see this as evidence of similar training data and optimization targets rather than architectural differences. In practice, ensemble strategies like majority voting between different models probably won't help much on the toughest questions.

To isolate these weaknesses, the team created a subset called SDE-hard with 86 particularly difficult questions. All standard models score below 0.12 accuracy there. Only GPT-5-pro, which costs twelve times more, reaches 0.224 and correctly answers nine questions where all others fail.

Project-level testing reveals more gaps

Beyond individual questions, the SDE framework also evaluates performance at the project level. Here, models work through a real scientific discovery cycle: formulating hypotheses, running experiments, and interpreting results to refine their hypotheses.

The eight projects examined range from protein design and gene editing to retrosynthesis, molecular optimization, and symbolic regression. The key finding: no single model dominates all projects. Leadership shifts depending on the task.

Surprisingly, strong question performance doesn't automatically translate to strong project performance. When optimizing transition metal complexes, GPT-5, Deepseek-R1, and Claude-Sonnet-4.5 find optimal solutions from millions of possibilities despite performing poorly on related knowledge questions. Conversely, models fail at retrosynthesis planning despite good question scores because their proposed synthesis paths don't actually work.

The researchers' interpretation: what matters isn't just precise specialist knowledge, but the ability to systematically explore large solution spaces and find promising approaches, even ones that weren't targeted from the start.

LLMs are far from scientific superintelligence but still useful

The study's conclusion is clear: no current language model comes close to scientific "superintelligence." But that doesn't mean they're useless. LLMs already perform well on specific projects, especially when paired with specialized tools and human guidance. They can plan and run experiments, sift through massive search spaces, and surface promising candidates that researchers might never have considered.

To close the gap, the researchers recommend shifting focus from pure scaling to targeted training for problem formulation and hypothesis generation. They also call for diversifying pre-training data to reduce shared error profiles, integrating tool use into training, and developing reinforcement learning strategies that specifically target scientific reasoning. Current optimizations for coding and math don't seem to transfer automatically to scientific discovery.

The framework and benchmark data will serve as a resource for pushing language model development toward scientific discovery. The study currently covers only four domains - fields like geosciences, social sciences, and engineering aren't included yet - but the framework's modular architecture allows for future expansion. The team has made the question-level code and evaluation scripts as well as project-level datasets publicly available.

A few days ago, OpenAI released its own benchmark, FrontierScience, designed to measure AI performance in science beyond simple question-and-answer tests. The result was similar: quiz knowledge doesn't equal research expertise.

AI News Without the Hype – Curated by Humans

As a THE DECODER subscriber, you get ad-free reading, our weekly AI newsletter, the exclusive "AI Radar" Frontier Report 6× per year, access to comments, and our complete archive.

Subscribe nowAI news without the hype

Curated by humans.

- Over 20 percent launch discount.

- Read without distractions – no Google ads.

- Access to comments and community discussions.

- Weekly AI newsletter.

- 6 times a year: “AI Radar” – deep dives on key AI topics.

- Up to 25 % off on KI Pro online events.

- Access to our full ten-year archive.

- Get the latest AI news from The Decoder.