Meta's Pixio proves simple pixel reconstruction can beat complex vision models

Key Points

- Meta AI has developed Pixio, an image model that learns by reconstructing hidden pixels, achieving better depth estimation and 3D reconstruction results than more complex models.

- The model uses a stronger decoder, larger masks, and special tokens to capture spatial structures and reflections—capabilities that are essential for understanding image content.

- Pixio was trained on two billion web images without being specifically optimized for benchmarks, yet still outperforms other approaches across various tasks.

Researchers at Meta AI have developed an image model that learns purely through pixel reconstruction. Pixio beats more complex methods for depth estimation and 3D reconstruction, despite having fewer parameters and a simpler training approach.

A common way to teach AI models to understand images is to hide parts of an image and have the model fill in the missing areas. To do this, the model has to learn what typically appears in images: shapes, colors, objects, and how they relate spatially.

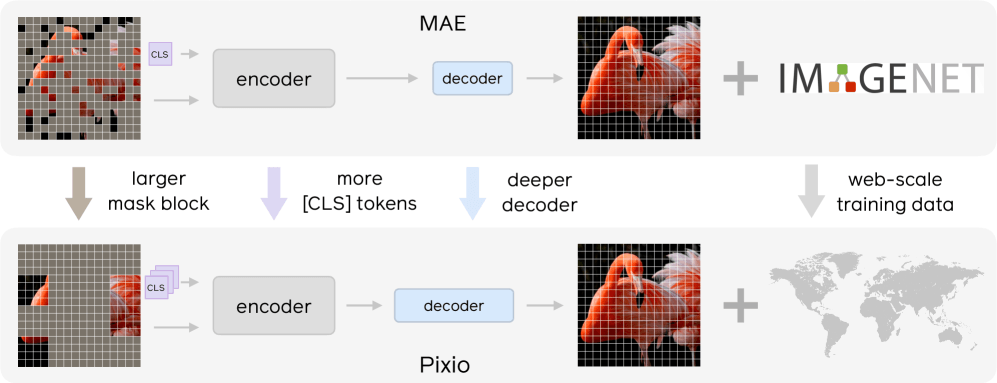

This technique, known as masked autoencoder (MAE), was recently considered inferior to more complex methods like DINOv2 or DINOv3. But a Meta AI research team has shown in a study that this isn't necessarily true: their improved Pixio model beats DINOv3 on several practical tasks.

Simpler training yields deeper scene understanding

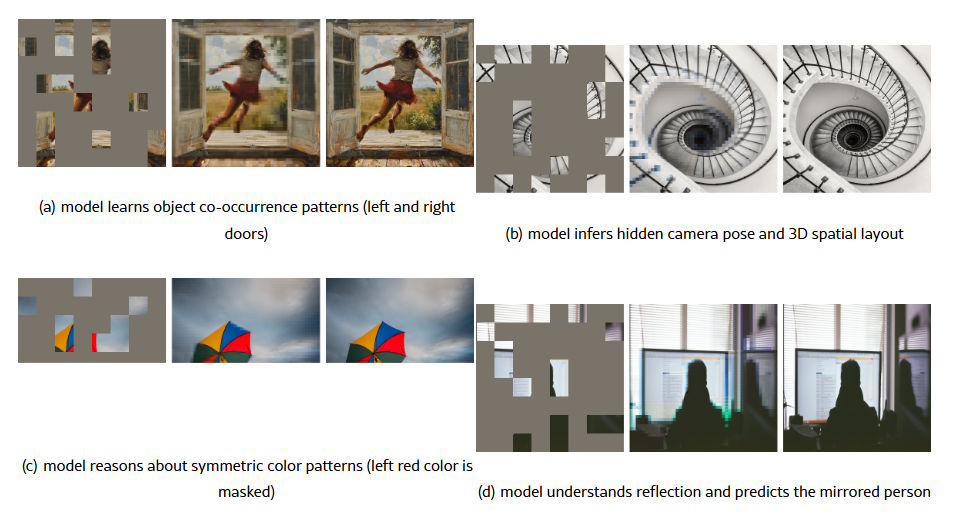

The researchers demonstrate Pixio's capabilities through examples of pixel reconstruction. When given heavily masked images, the model goes beyond reconstructing textures and captures the spatial arrangement of the scene. It recognizes symmetrical color patterns and understands reflections, even predicting a mirrored person in a window when that area was hidden.

These capabilities emerge because the model needs to understand what's visible to reconstruct it accurately: what objects are present, how the space is structured, and what patterns repeat.

Pixio builds on the MAE framework Meta introduced in 2021. The researchers identified weaknesses in the original design and made three major changes. First, they strengthened the decoder—the part of the model that reconstructs missing pixels. In the original MAE, the decoder was too shallow and weak, forcing the encoder to sacrifice representation quality for reconstruction.

Second, they enlarged the masked areas: instead of small individual squares, larger contiguous blocks are now hidden. This prevents the model from simply copying neighboring pixels and forces it to actually understand the image.

Third, they added multiple [CLS] tokens (class tokens)—special tokens placed at the beginning of the input that aggregate global properties during training. Each token stores information like scene type, camera angle, or lighting, helping the model learn more versatile image features.

Skipping benchmark optimization pays off

The team collected two billion images from the web for training. Unlike DINOv2 and DINOv3, the researchers deliberately avoided optimizing for specific test datasets. DINOv3, for example, inserts images from the well-known ImageNet dataset directly into its training data and uses them up to 100 times, making up around ten percent of total training data. This boosts results on ImageNet-based tests but could limit transferability to other tasks.

Pixio takes a simpler approach: images that are harder to reconstruct appear more frequently during training. Easy-to-predict product photos show up less often, while visually complex scenes appear more often.

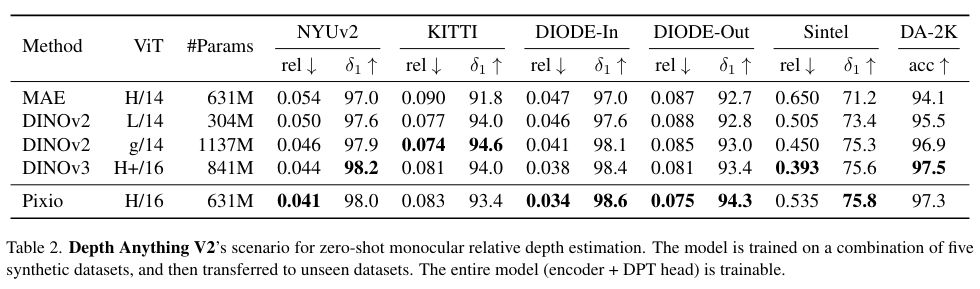

In benchmarks, Pixio with 631 million parameters often beats DINOv3 with 841 million parameters. For monocular depth estimation, calculating distances from a single photo, Pixio is 16 percent more accurate than DINOv3. It also outperforms DINOv3 in 3D reconstruction from photos, even though DINOv3 was trained with eight different views per scene while Pixio used only single images.

Pixio also leads in robotics learning, where robots need to infer actions from camera images: 78.4 percent compared to 75.3 percent for DINOv2.

Masking has its limits

The training method does have drawbacks. Hiding parts of an image is an artificial task since we see complete scenes in the real world, the researchers note. Low masking rates make the task too easy, while high rates leave too little context for meaningful reconstruction.

The researchers suggest video-based training as a potential next step. With videos, the model could learn to predict future frames from past ones; a more natural task that doesn't require artificial masking. The team has published the code on GitHub.

AI News Without the Hype – Curated by Humans

As a THE DECODER subscriber, you get ad-free reading, our weekly AI newsletter, the exclusive "AI Radar" Frontier Report 6× per year, access to comments, and our complete archive.

Subscribe now