Why AI still can't find that one concert photo you're looking for

Key Points

- Researchers from Renmin University of China and the Oppo Research Institute have developed DISBench, a benchmark designed to evaluate whether AI models can retrieve specific photos from personal collections based on contextual clues and relationships between multiple images.

- The findings are striking: even the top-performing model, Claude Opus 4.5, correctly identifies all relevant images in only about 29 percent of cases, highlighting significant shortcomings in current AI capabilities for this task.

- The core issue lies in poor planning ability—up to 50 percent of all errors stem from models correctly identifying the right context but then stopping the search too early or losing track of constraints along the way.

A new benchmark gives AI models a seemingly simple task: find specific photos in a personal collection.

When people look for a specific photo, they usually remember the context rather than the image itself. The concert photo where only the singer was visible, from the show with the blue and white logo at the entrance.

The key clue to which concert that actually was is hidden in a completely different image. According to a new study by researchers at Renmin University of China and the research institute of smartphone manufacturer Oppo, this is exactly where every standard image search system falls apart.

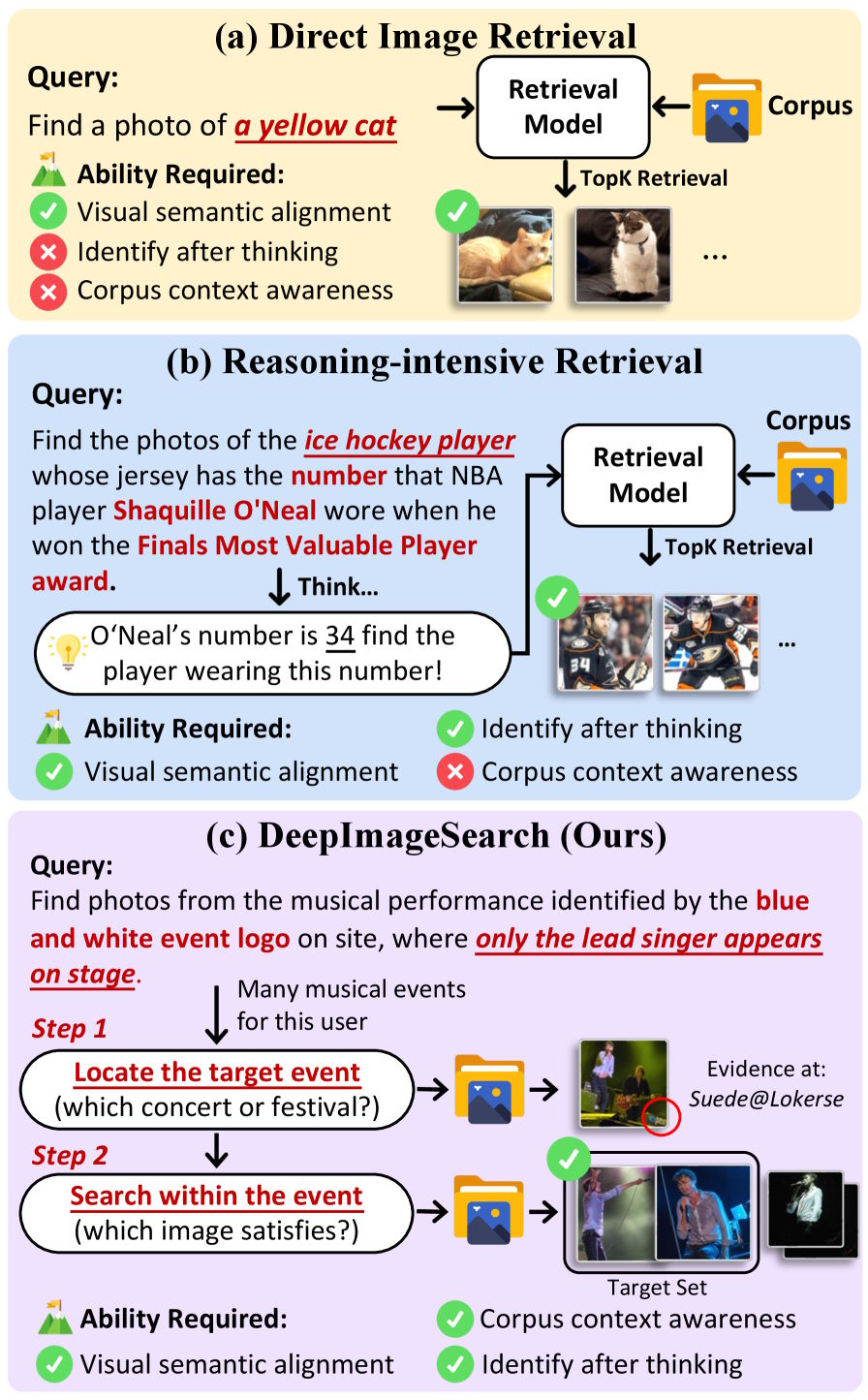

Today's multimodal search systems evaluate each image on its own: does it match the query or not? That works fine when the target photo is visually distinctive. But as soon as the answer depends on connections between multiple images, the approach hits a fundamental wall.

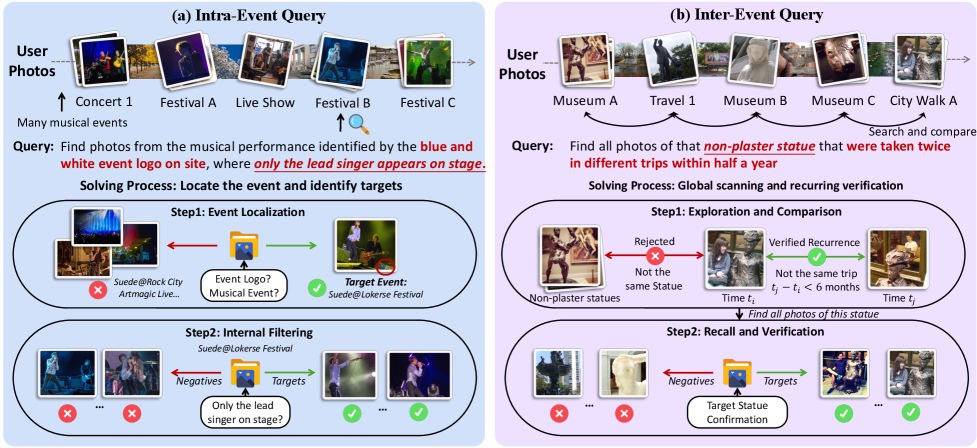

The researchers call their new approach DeepImageSearch and frame image search as an autonomous exploration task. Instead of matching individual images, an AI model navigates through a photo collection on its own, piecing together clues from different images to gradually reach its goal.

Current image search barely beats random chance

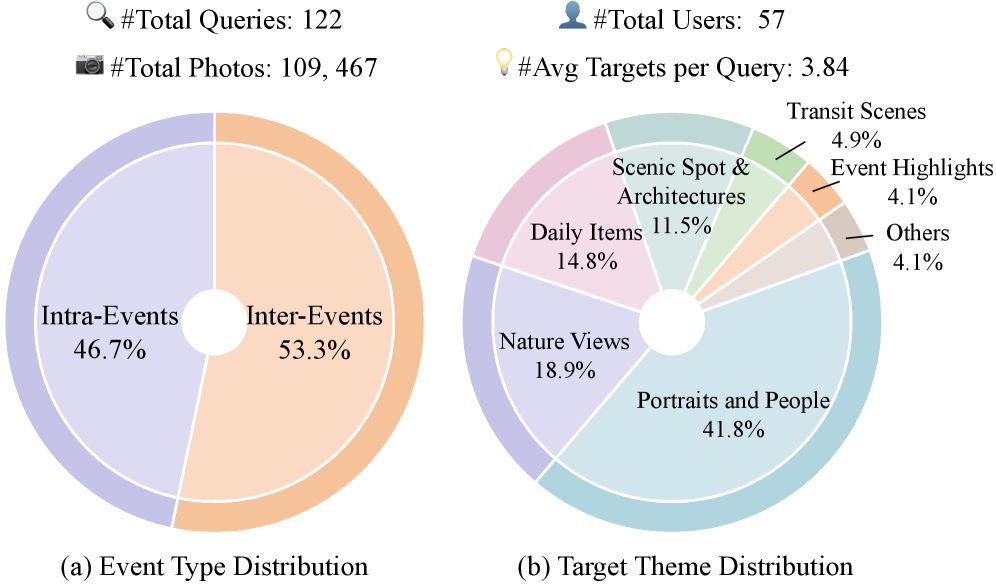

To show how wide the gap is between current technology and this kind of task, the researchers built the DISBench benchmark. It contains 122 search queries spread across the photo collections of 57 users with a total of more than 109,000 images. The photos come from the publicly licensed YFCC100M dataset and span an average of 3.4 years per user.

The search queries fall into two categories. The first requires identifying a specific event and then filtering out the correct images within it. The second is more demanding: the model has to detect recurring elements across several events and classify them by time or location. In both cases, looking at an image in isolation isn't enough.

The results from conventional embedding models like Qwen3-VL embedding or Seed 1.6 embedding show just how deep the problem runs. Only 10 to 14 percent of the top three results contain an image that was actually being searched for. Even those low numbers are largely due to chance, the researchers write.

Because personal photo collections contain many visually similar images from different situations, the models randomly fish out everything that superficially matches the query. They simply can't tell whether an image actually meets the contextual conditions.

Even with tool use, the best models struggle

For a fairer evaluation, the researchers developed the ImageSeeker framework. It gives multimodal models tools that go beyond simple image matching: semantic search, access to timestamps and GPS data, the ability to inspect individual photos directly, and a web search for unknown terms. Two memory mechanisms also help the models record intermediate results and keep track of long search paths.

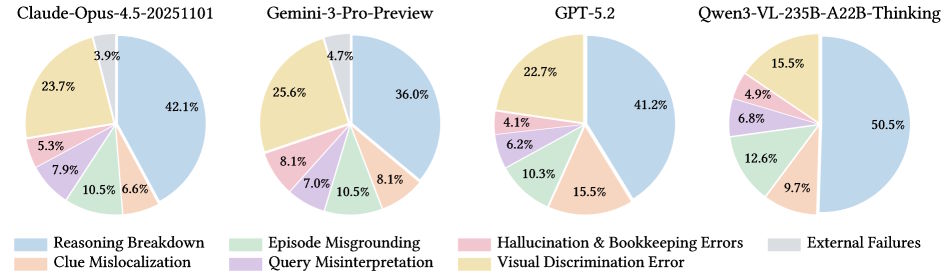

Even with all these tools, the results stay modest. The best model tested, Anthropic's Claude Opus 4.5, found exactly all the correct images in just under 29 percent of cases. OpenAI's GPT-5.2 managed about 13 percent, and Google's Gemini 3 Pro Preview hit around 25 percent. The open-source models Qwen3-VL and GLM-4.6V performed even worse. On conventional image search benchmarks, these same models score near-perfect results.

One experiment is particularly telling. When the researchers ran several parallel attempts per query and picked the best result each time, hit rates jumped by about 70 percent. The models clearly have the potential to solve these tasks; they just can't reliably find the right answer on any single try.

Models can see fine, they just can't plan

The researchers' manual error analysis reveals where the models actually break down. The most common failure by far is that models find the right context but then quit the search too early or lose track of their constraints.

The study calls this "reasoning breakdown," a pattern also observed in other contexts. Between 36 and 50 percent of all errors fall into this category. Visual discrimination—confusing similar-looking objects or buildings—comes in a distant second.

A systematic look at individual tools supports this finding. Of all the tools in the framework, the metadata tools have the biggest impact on performance. Without access to timestamps and location data, accuracy drops the most. Temporal and spatial context turns out to be the key factor in distinguishing visually similar images from different situations.

The researchers see their benchmark as a test case for the next generation of search systems. As long as AI models can only evaluate images in isolation, complex search queries in personal photo collections will remain unsolved. DeepImageSearch shows that models don't primarily need to see better; they need to plan better, track constraints, and manage intermediate results. The code and dataset are publicly available, along with a leaderboard.

As with text, AI models also exhibit the well-known "lost in the middle" problem with images: visual information at the beginning or end of a dataset gets more attention than information in the middle. The larger the dataset and the fuller the context window, the more pronounced this effect becomes. That's why good context engineering matters so much.

AI News Without the Hype – Curated by Humans

As a THE DECODER subscriber, you get ad-free reading, our weekly AI newsletter, the exclusive "AI Radar" Frontier Report 6× per year, access to comments, and our complete archive.

Subscribe now