70% of creative professionals fear stigma over AI use, Anthropic study finds

Key Points

- Anthropic's AI-supported interview tool shows that 97% of creative professionals save time and 68% see better work quality with AI, but 70% feel stigmatized when they use it.

- Many creatives worry about losing their livelihood to AI, with one voice actor sharing that parts of his industry have essentially died because of automation.

- While 91% of scientists want more AI help with research, trust is a problem: the time spent checking AI-generated results often cancels any efficiency gains.

A new Anthropic study shows creative professionals are benefiting from AI tools, but many hide their usage from colleagues and worry about losing their jobs to the technology.

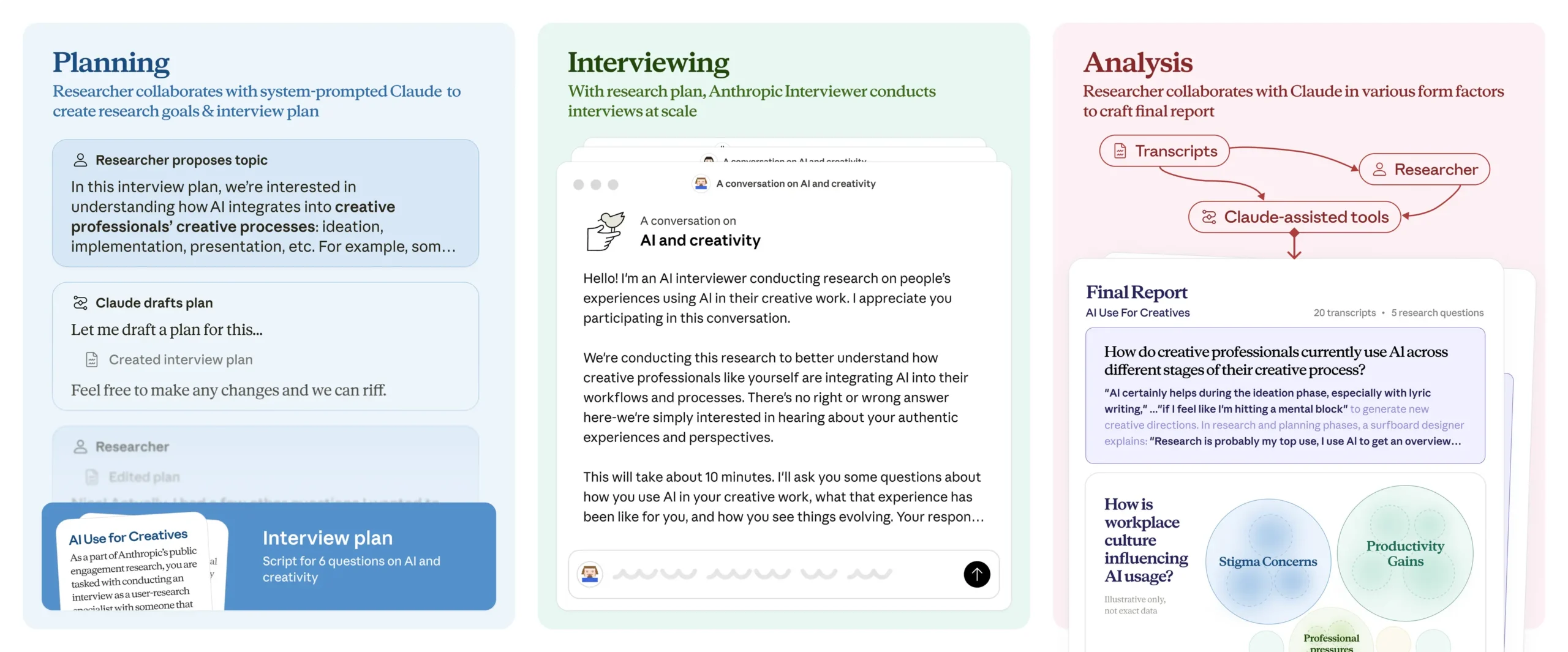

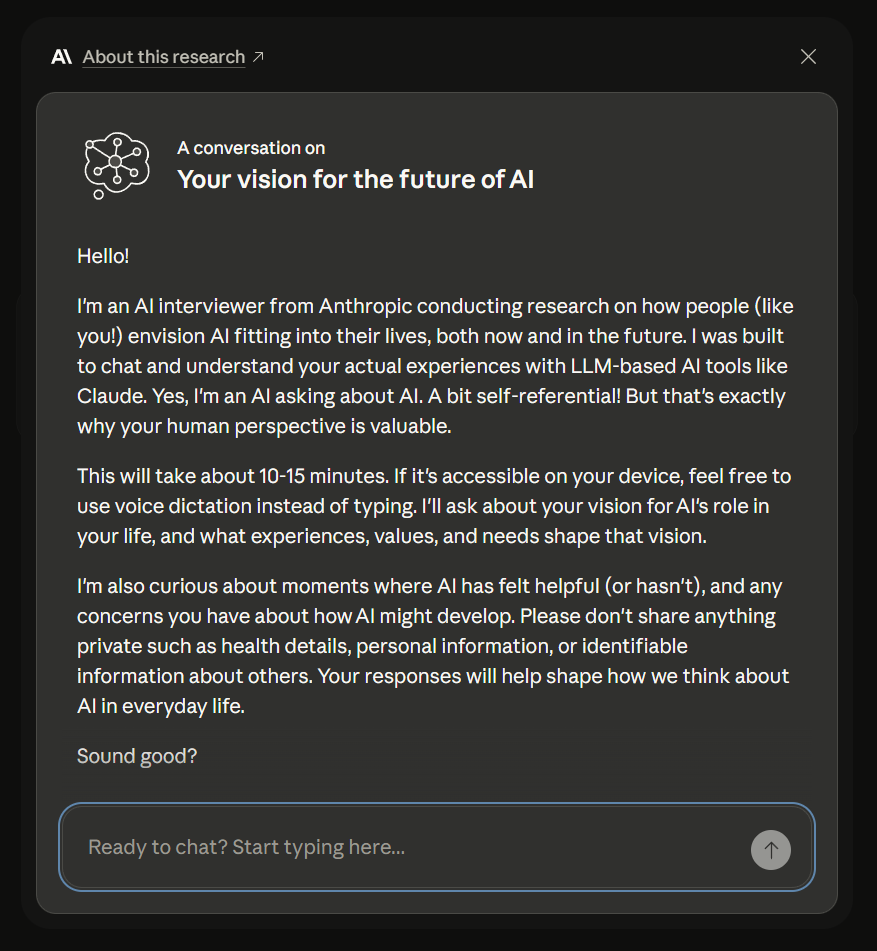

Anthropic has released a new research tool called Anthropic Interviewer and used it to survey 1,250 professionals about their AI use. The findings are mixed: while most respondents say AI has made them more productive, creative professionals in particular are dealing with social stigma and existential concerns.

The AI-powered interview tool conducted automated conversations with three groups: 1,000 workers from various industries, 125 scientists, and 125 creative professionals. Each interview lasted 10 to 15 minutes. Researchers then analyzed the results alongside Anthropic Interviewer, using an automated clustering tool to identify common themes and measure how often they came up.

Productivity gains come with social costs

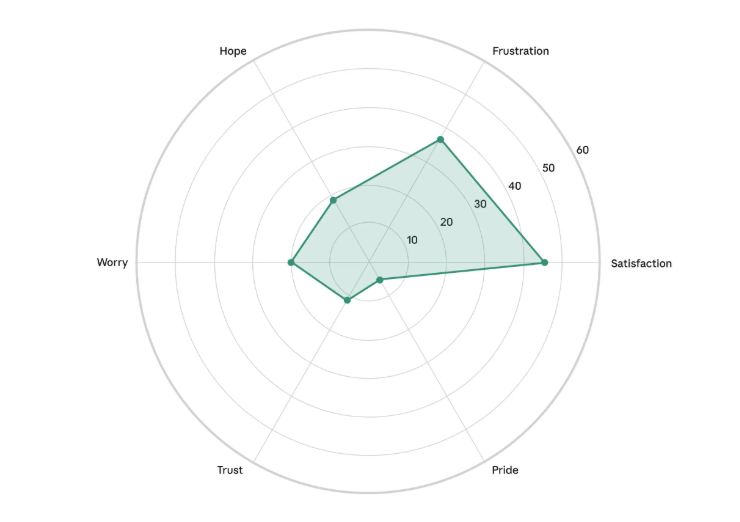

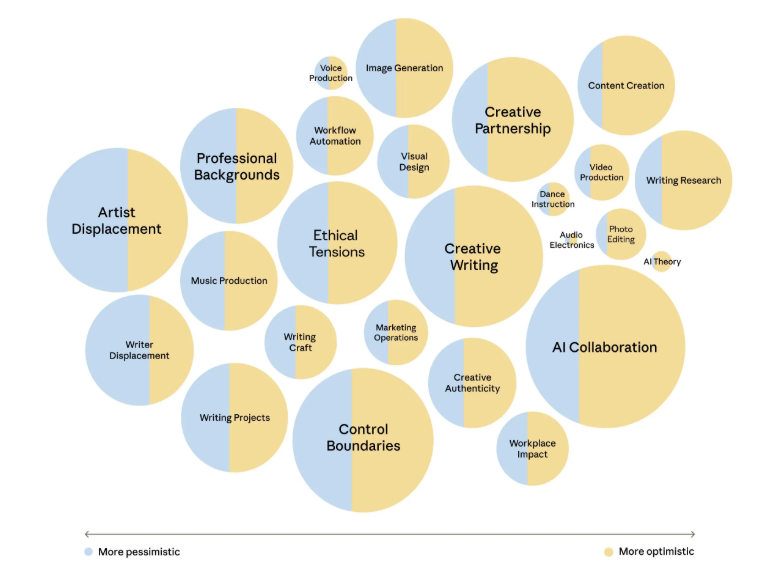

On the surface, the numbers for creative professions look good: 97 percent of creative professionals surveyed say AI saves them time, and 68 percent report that it has improved the quality of their work. One web content writer reported they've "gone from being able to produce 2,000 words of polished, professional content to well over 5,000 words each day." A photographer noted how AI handled routine editing tasks, reducing turnaround time from "12 weeks to about 3."

But these efficiency gains come at a cost. According to Anthropic, 70 percent of creative professionals mention dealing with stigma from colleagues. One map artist put it this way: "I don't want my brand and my business image to be so heavily tied to AI and the stigma that surrounds it."

The pattern holds across the general workforce too. 69 percent of respondents mention the social stigma around using AI at work. As one fact checker describes, "A colleague recently said they hate AI and I just said nothing. I don't tell anyone my process because I know how a lot of people feel about AI."

Economic anxiety runs deep among creatives

Economic concerns came up repeatedly in interviews with creative professionals, particularly around job displacement and the value of human creativity.

"Certain sectors of voice acting have essentially died due to the rise of AI, such as industrial voice acting," one voice actor said. A composer worried about platforms that might "leverage AI tech along with their publishing libraries [to] infinitely generate new music," flooding markets with cheap alternatives to human-produced work.

Another artist summed up the economic dilemma: "Realistically, I'm worried I'll need to keep using generative AI and even start selling generated content just to keep up in the marketplace so I can make a living."

One creative director was blunt about the tradeoffs: "I fully understand that my gain is another creative's loss. That product photographer that I used to have to pay $2,000 per day is now not getting my business."

All 125 creatives surveyed said they want to keep control over their creative work. In practice, though, that boundary gets blurry. Many admitted that AI ends up making creative decisions.

One artist said: "The AI is driving a good bit of the concepts; I simply try to guide it… 60% AI, 40% my ideas." A musician added, "I hate to admit it, but the plugin has most of the control when using this."

Scientists want AI partners they can trust

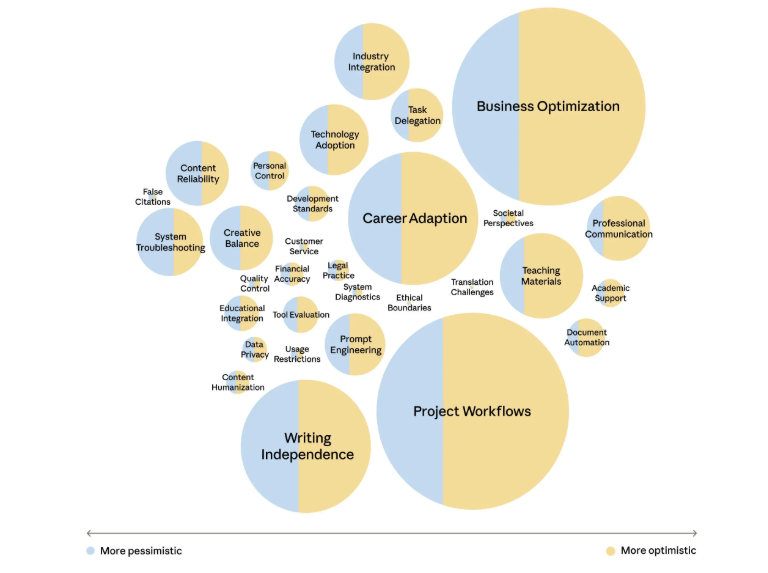

Scientists tell a different story. They mainly use AI for literature review, coding, and writing, but AI still can't reliably handle core research tasks like generating hypotheses and running experiments.

An information security researcher explained the problem: "If I have to double check and confirm every single detail the [AI] agent is giving me to make sure there are no mistakes, that kind of defeats the purpose of having the agent do this work in the first place." A mathematician agreed: "After I have to spend the time verifying the AI output, it basically ends up being the same [amount of] time."

Still, 91 percent of scientists want more AI support in their research. As one medical scientist put it, "I would love an AI which could feel like a valuable research partner… that could bring something new to the table."

Recent reports suggest generative AI is already making significant contributions to accelerating research.

Workers prefer collaboration, but automation is creeping in

In the study, 65 percent of respondents describe AI's role as augmentative, meaning humans and machines working together. The remaining 35 percent describe it as automation, where AI handles tasks directly.

This self-assessment differs from Anthropic's earlier analysis of actual Claude usage, which showed a nearly even split of 47 to 49 percent. Anthropic offers several explanations: users might edit Claude's outputs after chatting, use different AI providers for different tasks, or simply perceive their interactions as more collaborative than they actually are.

According to the study, 48 percent of respondents are thinking about switching to jobs focused on monitoring AI systems. One pastor said, "…if I use AI and up my skills with it, it can save me so much time on the admin side which will free me up to be with the people."

Anthropic rolls out AI-powered interview research

The company says it will now use the interview tool more broadly. Claude.ai users may start seeing pop-ups inviting them to participate in interviews. Anthropic plans to analyze and publish the anonymized findings as part of its social impact research.

The study has some methodological limitations that Anthropic acknowledges: participants were recruited through crowdworker platforms, which could introduce selection bias. They also knew an AI was interviewing them, which may have influenced their answers. The sample also primarily includes Western workers.

AI News Without the Hype – Curated by Humans

As a THE DECODER subscriber, you get ad-free reading, our weekly AI newsletter, the exclusive "AI Radar" Frontier Report 6× per year, access to comments, and our complete archive.

Subscribe now