Frontier Radar #1: From chatbots to problem solvers - the state of AI agents in 2026

Dear readers,

Welcome to the first issue of our Frontier Radar newsletter, where we take deep dives into key AI topics. We're kicking things off with AI agents, right where the industry is at a tipping point. Buzzword or paradigm shift?

What "agent" really means (and what it doesn't)

The term AI agent gets thrown around way too loosely. Microsoft, for example, spent months labeling glorified prompt templates as "agents" in Copilot. That's marketing that obscures what the technology can actually do.

The word comes from "agency" - the capacity to act. What sets agents apart from traditional LLM applications is that they orchestrate their processes dynamically and autonomously, using tools like web search, file access, and code execution within defined guardrails. They make their problem-solving process transparent and ask for user feedback when needed.

| Chatbot | Agent |

|---|---|

| Reacts to inputs | Breaks requests into subtasks |

| Uses tools when instructed | Chooses tools on its own |

| Human controls every step | Operates autonomously within guardrails |

| Black-box answers | Transparent problem-solving |

AI lab Anthropic defines agents like this:

Agents begin their work with either a command from, or interactive discussion with, the human user. Once the task is clear, agents plan and operate independently, potentially returning to the human for further information or judgement. During execution, it's crucial for the agents to gain “ground truth” from the environment at each step (such as tool call results or code execution) to assess its progress. Agents can then pause for human feedback at checkpoints or when encountering blockers. The task often terminates upon completion, but it’s also common to include stopping conditions (such as a maximum number of iterations) to maintain control.

Anthropic

Automation vs. agents: the gradual shift toward agentic AI

People often treat automation and agents as the same thing. That's not entirely wrong, since agents do involve an aspect of automation. But it's imprecise. Automation means executing a predetermined plan or workflow exactly as specified. An agent, on the other hand, designs that plan itself and then carries it out.

To put it sharply: agentic AI is the attempt to automate automation itself.

Everything becomes agentic

2025 was supposed to be the year of AI agents. By December, the takes started rolling in: the agentic revolution was a bust. People were still just chatting with AI models, not working alongside autonomous agents.

But that view misses something important: the models themselves have changed. They've been trained with agentic capabilities baked in. GPT 5.2 Thinking, Claude Opus 4.5, Gemini 3 Pro - they all generate plans in their reasoning traces, follow those plans, adapt them, and work toward their goals autonomously using tools.

The shift toward agentic AI never showed up as a single breakthrough product like ChatGPT, though there were attempts. Instead, it quietly crept into the models we're already using. Work with a current reasoning model, and you're working with an agent. Most people don't notice that part. What they notice is that the model can suddenly handle longer, messier tasks.

The demo video below shows what this looks like in practice. OpenAI's o3 gets tasked with analyzing an image. It recognizes what's in the image, searches the web for context, writes its own code to zoom in for a closer look, searches the web again, and only then gives its answer. No human laid out those steps. The model came up with the plan and ran it on its own.

Looking at releases like o3 and features like Deep Research, we'd argue the prediction that 2025 would be the year of agentic AI actually turned out to be right. The revolution happened, it was just quieter than anyone expected.

None of this makes automation obsolete, though. If anything, it's the opposite. Automation now wraps around agentic AI systems like a framework, giving you deliberate control over their behavior. That makes sense whenever you want to steer what the models can do rather than leave every decision up to them. Reliability is the main reason. Agents are powerful, but often not predictable enough. When you need control, you combine agentic capabilities with traditional automation.

| Assistant | Automation | AI Agent |

|---|---|---|

| Reacts to inputs | Executes predefined workflows | Breaks down goals on its own, works iteratively |

| Human controls every step | Runs automatically | Autonomous, asks when uncertain |

| No process planning | Follows the sequence exactly | Plans within boundaries |

| Human copies between tools | Integrates via fixed schema | Chooses tools on its own |

| Fast, flexible for text | Reliable for routine processes | Flexible for complex tasks |

| Inconsistent without clear instructions | Fails on exceptions | Error-prone without guardrails |

| Drafts, Q&A, brainstorming | Data sync, routine tasks | Research chains, multi-step workflows |

Part of this strategy can involve networking multiple agentic AI models together. This makes the AI process more controllable and transparent at a granular level. Instead of giving one agent full responsibility, you orchestrate multiple specialized agents that check and complement each other.

Agentic AI systems: harness engineering

In practice, success or failure depends not just on the model but on the combination of model, tools, and the technical scaffolding around them. The longer an agent runs, the less a prompt plus tool list will cut it.

What you need instead is a harness: a systematic framework of code, memory, tool interfaces, and rules.

The model generates plans, tool calls, and responses but doesn't actually execute anything. The tools are concrete capabilities like file access, shell commands, or Git operations.

The harness is the crucial part: it assembles the prompt, executes tool calls, enforces security rules, and maintains continuity across sessions.

The basic structure: the agent loop

At their core, agentic systems almost always follow the same flow, which OpenAI describes in detail in its Codex CLI documentation.

It starts with user input, and the harness builds a prompt from it. The model responds either with a final answer or a tool call. If it's a tool call, the harness executes it, appends the result to the context, and queries the model again. This repeats until the model delivers a response to the user.

The prompt itself is a stack of layers: system rules, developer rules, project rules, user instructions, conversation history, and tool results.

Many systems also append context data: the current working directory, relevant files like README or architecture docs, tool definitions, and environment info like sandbox mode or network access.

The harness has to assemble these layers reliably, or the agent drifts or forgets rules.

The context window as a scarce resource

Every model has a limited context window. Since the prompt grows with each tool call, the system runs into problems without countermeasures: the agent forgets early decisions, contradicts itself, or abandons implementations midway.

There are a few ways to deal with this. Prompt caching reuses identical prompt beginnings for more efficient requests. Compression summarizes old details and replaces the full history with more compact representations, though information can get lost in the process.

Memory across sessions

Another major problem with long-running work is that each new session starts without memory. Without countermeasures, agents try to do too much at once and leave work half-finished, or later sessions prematurely declare the task complete.

Anthropic's Claude Code solves this through explicit handoff artifacts: an initializing agent sets up a progress file and an initial Git commit. Subsequent agents work incrementally and update these artifacts. Continuity doesn't live in the model but in files that new sessions can quickly pick up.

Claude Code typically uses CLAUDE.md files for instructions and context that are loaded at startup. These can be global in the home directory, project-wide in the repository, or local for private settings. Optionally, there are also subagents as separate files for division of labor.

Project-specific instructions as an open standard

OpenAI takes a similar approach with Codex CLI. AGENTS.md files in the project automatically flow into the prompt and contain coding standards, architecture principles, or testing rules. The format has evolved into an open standard supported by OpenAI, Google Jules, and Cursor, and managed by the Linux Foundation.

On top of that, the harness enforces security rules: which directories are writable, whether network access is allowed, when user approval is required. The model may request, the harness decides whether it's permitted.

A well-built harness guides the agent toward robust behavior: clear intermediate steps, stable rules, connectable handoffs, security through sandbox and approval requirements. This cushions typical problems like creeping context loss, infinite loops, hallucinated assumptions, and premature completion claims.

| Aspect | Human + Language Model | Human + AI Agent |

|---|---|---|

| Basic principle | Dialog/prompt → model generates response/draft | Task/goal → agent plans steps, uses tools, iterates, delivers result + evidence |

| Role of AI | Generator and sparring partner (text, ideas, structure, code) | Executing problem solver (task management, research chains, tool actions) |

| Intention (who defines what?) | Human defines goal mostly prompt by prompt | Human defines outcome + success criteria; agent derives subtasks |

| Control | Prompting, manual iterations, copy/paste between tools | Orchestration: rules/policies, tool permissions, budgets/timeouts, checkpoints, monitoring |

| Responsibility | Human checks/decides at the end (facts, legal, brand) | Human sets guardrails + approvals; agent documents, escalates when uncertain; final responsibility stays with human |

| Input | Prompt + possibly provided sources/notes | Mission/briefing + constraints + access to systems/sources + definition of done |

| Production | Mostly single-step (responses/drafts), little process continuity | Multi-stage: plan → execute → check → improve → possibly ask back/escalate |

| Tool/system use | Optional, usually executed by human (search, spreadsheets, CMS) | Agent uses tools on its own within permissions (web search, DB, CMS, tickets, scripts, etc.) |

| Output | Draft/variant/response (often without verifiable evidence) | Result + variants + sources/logs + open items + next steps (more auditable) |

| Typical strengths | Fast text creation, ideas, phrasing, summaries | Repeatable workflows, research/analysis chains, partially automated processes, "work packages" |

| Typical risks | Hallucinations, missing sources, high rework share | Wrong tool actions/overreach, permission/compliance risks → needs guardrails and approvals |

A concrete example of how important harness engineering and clean context are comes from OpenAI's internal Data Agent: a tool that helps employees get reliable data answers in minutes instead of days. What matters is the environment around the model: the agent uses multiple context layers (table metadata and query history, human annotations, code-based explanations of data tables, internal knowledge from Slack/Docs/Notion, memory, and live queries) while working with strict permission checks and traceable results.

From chatbot to task solver

As described above, AI agents independently take on multi-step tasks and coordinate complex workflows—unlike traditional chatbots that react to individual requests and deliver isolated answers. The goal is ambitious: automating large parts of knowledge work.

Only if this succeeds can the enormous investments in the technology pay off. OpenAI, for example, wants to sell AI agents at prices equivalent to several full-time salaries, or take over and accelerate large parts of scientific research. Think of these agents as industrial robots, but for the computer. The narrative that humans and machines work together will only hold as long as the systems can't create better solutions on their own.

According to a comprehensive study by UC Berkeley, Stanford University, IBM Research, and other institutions ("Measuring Agents in Production") from December 2025, productivity and efficiency gains are the main reason companies deploy agents in areas like insurance, HR, or analysis workflows. The findings are based on a survey of 306 practitioners and 20 in-depth interviews with teams already using agents in production.

New benchmarks: working time and efficiency

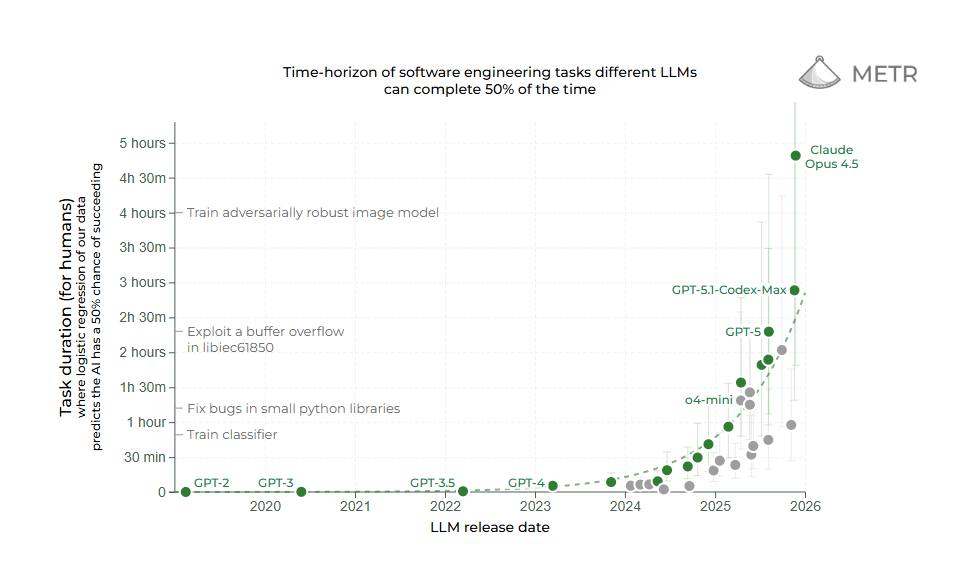

Organizations like METR (Model Evaluation and Threat Research) are developing benchmarks that specifically measure how well AI systems can autonomously handle longer, coherent tasks. These evaluations focus on planning ability, error correction, and efficient use of work time, metrics that matter most for automating knowledge work.

Current results show clear progress: according to METR measurements, leading AI models can now handle tasks that would take a human expert about 50 minutes. That's a significant jump from earlier model generations. Performance doubles roughly every seven months, measured by the complexity of tasks they can solve. The curve points steeply upward.

However, the benchmarks also reveal clear limits: for tasks requiring several hours of concentrated human work, AI systems' success rates drop drastically. Current agents struggle especially with tasks that require iterative problem-solving, recognizing and correcting their own errors, or navigating unexpected obstacles. The models tend to lose context on longer task chains or get stuck in dead ends. The last stretch to true autonomy is the hardest.

Reliability and security: the Achilles heels of agentic AI

The main problem with implementing agentic AI remains reliability. Cybersecurity adds another layer, particularly the ever-present threat of prompt injections.

Since AI models don't work deterministically, ensuring their correctness is difficult. In a ranking of development hurdles, respondents most frequently cite "Core Technical Performance"—meaning robustness, reliability, scalability, latency, and resource efficiency—as the greatest challenge. The model can be brilliant, but if it fails one out of ten times, it's unusable for critical processes.

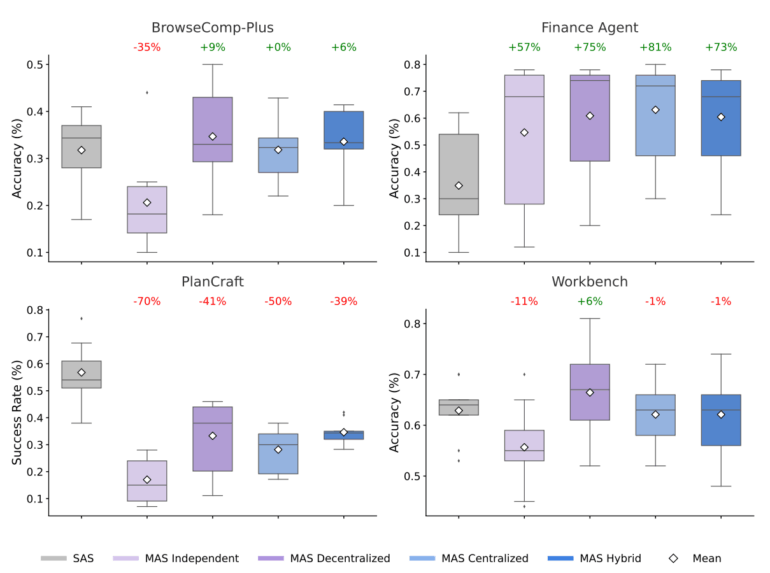

Multi-agent systems that break tasks into smaller pieces across multiple agents to increase controllability and transparency aren't a universal solution either. A recent study from Google Research, Google DeepMind, and MIT with 180 experiments shows that multi-agent performance varies by task from significant improvement to massive deterioration.

When each step changes the state, coordination can fragment the context. The rule of thumb from the study is that above roughly 45 percent single-agent success rate, coordination often no longer pays off. More agents doesn't automatically mean better results. We'll take a closer look at the study below.

For cybersecurity in agentic AI systems, prompt injection represents the central and so far unsolved threat. This vulnerability is technical in nature and lies in the architecture of language models themselves. They cannot reliably distinguish between legitimate user instructions and malicious injected commands. The problem has been known since at least GPT-3 and hasn't been eliminated despite many attempts.

A comprehensive red-teaming study from mid-August 2025 with nearly 2,000 participants and 1.8 million attacks on AI agents shows the scale of the security gap. Over 62,000 attempts successfully led to policy violations like unauthorized data access, illegal financial actions, and violations of regulatory requirements. The study achieved a 100 percent behavioral success rate. In other words, every single agent could be compromised.

Numbers from Anthropic on Opus 4.5, the engine behind tools like Claude Code, also show that the model can be cracked via prompt injection in about 30 percent of cases across ten attack attempts. From a cybersecurity perspective, these are alarming results, an error rate that's simply unacceptable for security-critical applications.

These risks can currently only be mitigated by deliberately limiting the systems' capabilities, whether through stricter system specifications, restrictive access rules, limited tool use, or additional human confirmation steps.

The flip side is that the more autonomously and capably an AI agent is supposed to act, the larger its attack surface becomes. Companies face a fundamental trade-off between productivity gains and security risk. Anyone who wants to automate everything using agentic AI alone opens doors.

Hype meets reality

Instead of fully autonomous "AI employees," simple, heavily constrained systems still dominate according to the MAD study. These work with frontier language models, sometimes very long prompts, and close human oversight. Thanks to the agentic capabilities of the models, AI agents have made their way in. But these are relatively simple implementations, not complex, multi-stage AI systems combined with automation.

Put simply, a lot of human input is still necessary. Above all, the interaction between agents or between agents and software needs work. Almost all agents report to humans. The vision of the autonomous digital colleague remains exactly that for now: a vision.

The next frontier: hundreds of agents, RL, and the new startup landscape

Agent swarms as a solution for complex problems?

We described how Anthropic built a thoughtfully constructed framework with Claude Code, the system around the model. Initializing agents, subagents, precise function calls: everything is designed to avoid problems like creeping context loss and stuck agents.

However, the agentics study we referenced above paints a much more nuanced picture: multi-agent systems don't automatically add value. In many scenarios, they actually perform worse than a single powerful agent with tools.

They help primarily when three conditions are met:

- The work can be broken into largely independent subtasks that can be processed in parallel.

- Good, automatable feedback signals exist for these subtasks (tests, numbers, external validators).

- The single-agent baseline isn't "too good" yet. Above roughly 45 percent success rate for the single agent, scaling effects tip because the coordination overhead and error amplification eat up the gains.

The finance benchmark in the study shows this clearly. A research task gets broken into news analysis, SEC filings, key metrics, and risk scenarios. Multiple specialized agents work in parallel while a central coordinator checks and integrates the results. The result is a performance boost of about 80 percent over the best single agent. This works because financial analyses can be broken into independent subtasks—revenue trends, cost structures, and market comparisons can be analyzed separately and then combined.

For highly sequential tasks like planning or step-by-step procedures, the opposite happens. All multi-agent variants worsen performance by 40 to 70 percent. Planning tasks require a strictly sequential flow where each action changes the state that all subsequent actions build on. When multiple agents handle such tasks, a coherent chain gets artificially split. This creates significant coordination overhead that consumes the compute budget for actual problem-solving without adding value.

Applied to software development, the study suggests that multi-agent systems help primarily with large, easily decomposable codebases where independent subtasks can be processed in parallel. This applies to migration waves across hundreds of files, parallel performance experiments, or research-heavy tasks.

At the same time, the study warns against too much agentics in exactly the situations where coding already works well with a strong single agent—when the task is fundamentally sequential (a delicate refactor, a complex pipeline) or the single agent already achieves very high hit rates. It becomes especially problematic when individual subtasks themselves require many tool calls. Then the coordination overhead between agents consumes the compute budget each agent would need for its own work.

Cursor and scaled agents

Cursor, the AI-powered code editor, built a harness for agents and ran a relevant experiment: up to 2,000 coding agents worked in parallel on a shared project for nearly a week. According to Cursor, billions to trillions of tokens flowed through the system across all attempts. The team chose a web browser as their showcase project—not because they wanted to build the "Chrome killer," but deliberately as a massive yet clearly specified goal for exploring agent coordination: the agents were supposed to develop a new rendering engine in Rust, with HTML parsing, CSS cascade, layout, text shaping, painting, and JavaScript VM. At the end, according to the blog post, there were over one million lines of code. The CEO even mentioned three million on X.

A look at the GitHub repo paints a more complex picture: FastRender is an experimental prototype that relies heavily on existing components. These include html5ever and cssparser from the Servo project (an open-source browser engine) as well as a JavaScript engine that Wilson Lin, the responsible developer at Cursor, had already developed in a separate agent experiment project.

In an interview with Simon Willison, Lin admitted that the agents chose these dependencies themselves because he hadn't explicitly specified in his instructions what they should implement from scratch.

Parts of the code also closely resemble existing Servo implementations; the codebase is difficult to navigate, according to developers, and for a long time the project couldn't compile on many systems.

This led to fierce criticism in the developer community. Commenters call it "AI slop" and accuse Cursor of selling the result as an autonomously created browser built from scratch when a significant portion actually relies on existing libraries. The blog Pivot to AI sums it up bluntly as a "marketing stunt." Cursor itself emphasizes that FastRender was never intended as a product but as a research project on coordinating agent swarms.

Experience reports now show that FastRender can actually build on some systems and can rudimentarily display simple pages like Wikipedia or CNN, but as an unstable prototype, not a full-fledged browser.

What's interesting is how quickly a counter-movement emerged. In response to the criticism, a single developer (embedding-shapes) built a much smaller browser prototype with a single Codex agent in three days, about 20,000 lines of Rust.

Simon Willison puts it well in his comment on HackerNews. He had initially seen FastRender as the first real example where thousands of agents accomplish something that couldn't be done otherwise. Then the single-agent approach showed that one strong agent plus an experienced human can tackle a similar problem space without an agent swarm.

For the debate about agentic AI, this is instructive. The Cursor experiment shows how difficult it is to control, evaluate, and above all understand the performance of thousands of agents over many days. The agentics study provides a possible theoretical framework for this, even though it only examined systems with up to nine agents. Tasks that can only be partially broken into independent steps lie exactly in the range where multiple agents easily create more coordination overhead and error amplification than actual value. With thousands of agents over days, these effects are likely even more pronounced.

The "one human plus one agent" project suggests that a well-designed framework, clear specifications, and human guidance often accomplish more than an agent swarm with a massive token budget. Multi-agent systems aren't a cure-all but a specialized tool for certain problem classes.

The two projects aren't directly comparable, of course. FastRender had broader ambitions (its own JavaScript engine, more features) but delegated much to existing libraries. The basic functionality—rudimentarily displaying simple web pages—was both achieved.

Then there's the question of cost-effectiveness. With billions to trillions of tokens, the costs for the FastRender experiment likely ran into the high five to six figures. Cursor hasn't published exact numbers. Compare that to embedding-shapes with a fraction of the resources.

The agentics study supports this pattern quantitatively. Single agents achieve up to five times more successful tasks per 1,000 tokens than the most complex multi-agent architectures. Anyone not primarily doing basic research but needing robust results under cost pressure often does better with a strong single agent plus human guidance.

What Cursor learned

What's most interesting is what Cursor learned, because it shows how multi-agent systems can be used sensibly and where their limits lie.

Flat hierarchies fail

Equal agents with a shared coordination file didn't work. 20 agents effectively slowed down to the throughput of two or three. Without hierarchy, agents became risk-averse, making small, safe changes instead of tackling difficult tasks.

This aligns with the agentics study. Independent agents without a clear central node amplify errors most strongly and perform worst on sequential tasks.

So just using more agents alone solves nothing. Without structure, communication costs and misunderstandings dominate.

Role separation works

The solution Cursor arrived at resembles what Anthropic describes for Claude Code and what the agentics study models as "centralized" or "hybrid" architecture. Planners create tasks and can spawn additional subplanners. Workers execute the task packages. At the end of a cycle, a higher-level instance evaluates whether to continue or change course.

Wilson Lin describes in the interview what this looked like for FastRender. One planner handled CSS layout, another handled performance. Workers implemented specific functions. Tests and the compiler provided feedback.

This fits the positive study results in finance. Where tasks can be cleanly broken into subtasks with their own verification mechanisms, such a hierarchy can actually increase throughput.

Less is more

An additional integrator role for comprehensive quality control created more problems than it solved in Cursor's experiment. Workers could handle many conflicts locally themselves. The framework deliberately allowed some slack. Temporary compile errors were acceptable as long as they quickly disappeared and overall throughput was good. Lin explained it in the interview this way: if you demand that every single commit compiles perfectly, you create a bottleneck in coordination between agents. Instead, there was a stable error rate that didn't escalate but got corrected after a few commits.

The study warns against exactly this excess of structure. Hybrid, very complex topologies cause high coordination costs, especially when many tool calls are needed. Fewer layers, clearer responsibilities, and simple escalation paths are often more robust than a perfectly planned but overloaded orchestrator.

However, this only works if errors actually get corrected. The criticism of FastRender relates to the fact that this mechanism apparently didn't work consistently.

Model choice matters

In the Cursor experiments, GPT-5.2 proved more stable than specialized coding models on long tasks, with less drifting from the actual goal and more complete implementations over many cycles.

Lin explains this by saying that instructions for such systems go beyond pure programming. The agents must understand how to operate independently in a framework, how to work without constant user feedback, and when to stop.

The study describes the same effect more abstractly. The higher the model's base capability, the less additional agents can extract. And the more important it becomes that coordination doesn't slow down the model. A weaker model can visibly benefit from smart architecture. For top models, the gain is smaller and more easily consumed by coordination overhead.

Instructions remain central

Most system behavior still depends on how the agents are instructed. This applies both at Cursor and in the study's benchmarks. Who plans, who works, who validates, how errors are handled, how much parallelization is allowed. Everything is ultimately behavioral rules cast in text.

Lin emphasized in the interview how much time went into revising these instructions. Some earlier architectures failed not because of technical limits but because of wrong instructions. Coordination, avoiding dead ends, focus over long periods. This comes from good instructions, not agent magic.

Even with highly automated systems with thousands of workers, human input remains crucial. This includes choosing the task, formulating the instructions, deciding when an agent swarm really makes sense and when a single strong agent plus an experienced developer is perfectly sufficient.

The next lever: RL environments for code and agent coordination

Besides the harness, there's a second lever: how the models themselves are trained. Here, the major AI labs are currently investing heavily in learning environments for agents. The basis is reinforcement learning: the model tries something, gets feedback on whether it worked or not, and adjusts its behavior accordingly.

Code and software are particularly well-suited for such "reinforcement learning gyms": whether a solution works can be automatically verified through tests, and intermediate steps can be tested too. That means clear feedback and fast iterations.

According to The Information, Anthropic has internally discussed investing over a billion dollars in such agentic training environments in the coming year. Startups like Mechanize (reportedly already working with Anthropic) are positioning themselves in the emerging market.

The logic is simple. Better training environments lead to models that work more reliably in systems like Claude Code or Cursor. Whether this pans out remains to be seen. This application of reinforcement learning sometimes has problems with transfer to new situations and with so-called reward hacking, meaning agents find loopholes to maximize their reward signals instead of solving the actual task. But the investments suggest AI companies are convinced these problems can at least partially be solved.

Training for collaboration

A related approach goes one step further: training models not just for better coding but explicitly for coordination with other agents. The problems with agent swarms we described above could also stem from the fact that today's models simply weren't optimized for collaboration.

Chinese company Moonshot AI has introduced Kimi K2.5, a model that takes this path. According to the manufacturer, it can orchestrate up to 100 subagents and coordinate parallel workflows with up to 1,500 tool calls. Compared to a single agent, this is supposed to reduce execution time by a factor of 4.5.

However, the swarm function is still in beta, and the impressive numbers come from Moonshot's own internal benchmarks. Independent tests of swarm coordination are still pending. Early user reports suggest the function works reliably on clearly structured tasks but drops off significantly with unclear specifications or poorly defined tools.

The interesting question behind this is whether explicit coordination training could solve the problems the agentics study documents. That depends on where the problems come from.

For tasks that decompose well, explicit coordination training could help. Agents that communicate more sparingly, catch errors earlier, and better assess when parallelization makes sense would address exactly the bottlenecks the paper describes. This hasn't been proven yet.

For structurally sequential tasks, the problem runs deeper. There, additional agents worsen results across all architectures. The study suggests such tasks can hardly be meaningfully decomposed. More efficient communication alone probably won't change that.

More thinking time, better results

Learning environments improve models during training. But there's a second lever: how much compute time the model can spend on a task during application. More thinking time often means better results.

According to Andrej Karpathy, the performance progress in 2025 was primarily defined by longer training runs with reinforcement learning, not by larger models. Additionally, we got a new dial: longer chains of thought and more compute time during application. OpenAI's o1 was the first demonstration, but o3 was the turning point where you could really feel the difference.

The results are measurable, though they should be interpreted with caution. At the International Informatics Olympiad 2025, an OpenAI system in the separate AI track reached gold level and placed sixth among 330 human participants. Only five humans did better. At the ICPC World Finals 2025, OpenAI's system solved all twelve problems. The best human team managed eleven.

However, the AI systems competed in separate tracks in both cases and used ensemble approaches with multiple models. These are impressive benchmarks, but they show peak performance under controlled conditions, not yet everyday coding work.

Three scenarios: baseline, acceleration, slowdown

AI agents didn't establish themselves as the one revolutionary product in 2025, but they've long since become part of everyday life through the massively increased capabilities of current reasoning models like GPT-5.2 Thinking or Claude Opus 4.5.

The technology is here, but the hurdles are shifting. Instead of failing due to model intelligence, broad deployment often stumbles on reliability for complex, sequential tasks and unsolved security risks like prompt injections. The key to success no longer lies in the model itself but in harness engineering, systematically building a controlled environment that enables autonomy without sacrificing security.

Scenario 1: The engineering evolution (baseline)

Development continues at the current pace. Focus shifts away from "magical" new models toward harness engineering as an industry standard. Companies accept that models alone are unreliable and build robust frameworks around them, with context management, memory, and guardrails to work around problems like context erosion.

Multi-agent systems establish themselves in niches with clear task division (software migrations, for example), while humans remain closely involved. Almost all agents still report to humans, and approval steps are standard. The trade-off between autonomy and security persists. Prompt injection isn't technically solved but mitigated through process design and human-in-the-loop approaches.

Scenario 2: The RL breakthrough (acceleration)

The massive investments in reinforcement learning environments driven by Anthropic and OpenAI pay off faster than expected. Agents learn in simulated environments ("gyms") to correct their own errors and recognize dead ends early. This makes them reliable even for long, sequential tasks. New model architectures largely defuse the prompt injection problem, clearing the way for true autonomy in sensitive data areas. The vision of AI agents autonomously taking over entire jobs or research areas comes within reach.

Scenario 3: The autonomy pullback (deceleration)

The limits described in this article prove more stubborn than expected. RL training hits fundamental problems like reward hacking (agents trick the reward system) and lack of generalization. Additionally, spectacular security incidents from prompt injections lead to strict regulatory restrictions or internal company freezes.

The realization that large agent swarms are often less efficient than single models leads to disillusionment. Companies deliberately limit the autonomy of their systems and return to tightly controlled assistants with strong human oversight instead of betting on autonomous agents.

Our perspective

The baseline scenario is most likely, with a tendency toward acceleration in the code domain. Investments in training environments will continue to rise, and the code domain benefits especially because success can be verified through automated tests. Similarly suitable are structured workflows in insurance, HR, or analysis, where tasks can be parallelized and success criteria can be clearly defined.

Less suitable are domains with a high degree of discretion, regulatory requirements, or reputational risks. Here, intensive human oversight remains indispensable, which largely consumes the efficiency gains from automation.

At the same time, security problems remain fundamentally unsolved. A 30 percent success rate for prompt injection attacks is unacceptable for critical applications.

Looking toward 2026, the key takeaway remains that the system around the model makes the difference, not the model alone. Anyone investing in agentic AI should prioritize harness engineering and start with narrowly defined tasks and built-in approval steps. Fully autonomous digital colleagues remain a vision for now.

Ground truth: sources & deep dives

External sources:

- Microsoft / Copilot Agents

- Anthropic / Effective Agents

- OpenAI / Deep Research

- OpenAI / Codex Agent Loop

- OpenAI / In-House Data Agent

- Anthropic / Long-term agents

- METR / AI task measurement

- Cursor / Scaled agents

- YouTube / Wilson Lin Interview

- GitHub / FastRender Issues

- Pivot to AI / Cursor critique

- embedding-shapes / One-Agent-Browser

- HackerNews / Willison comment

- The Information / AI coworker

- Kimi / K2.5 model

THE DECODER article:

AI News Without the Hype – Curated by Humans

As a THE DECODER subscriber, you get ad-free reading, our weekly AI newsletter, the exclusive "AI Radar" Frontier Report 6× per year, access to comments, and our complete archive.

Subscribe nowAI news without the hype

Curated by humans.

- Over 20 percent launch discount.

- Read without distractions – no Google ads.

- Access to comments and community discussions.

- Weekly AI newsletter.

- 6 times a year: “AI Radar” – deep dives on key AI topics.

- Up to 25 % off on KI Pro online events.

- Access to our full ten-year archive.

- Get the latest AI news from The Decoder.