Google Deepmind's new bioacoustic model shows the power of generalization by detecting whales with bird training

Key Points

- A bioacoustic model from Google Deepmind, originally trained primarily on bird calls, surprisingly outperforms specialized whale models when it comes to recognizing whale songs.

- The researchers attribute this transfer to the fact that bird classification demands extremely fine-grained acoustic distinctions, and that birds and marine mammals have evolved similar sound production mechanisms.

- Building on the model, classifiers for newly discovered sound types can be trained within just a few hours, a significant advantage in marine bioacoustics, where new sounds are sometimes only attributed to a specific species decades after their initial recording.

A general-purpose bioacoustic model from Google Deepmind, trained mostly on bird calls, consistently beats models specifically built to classify whale sounds. The reason traces back to evolutionary biology.

Because visual contact underwater is often impossible, researchers can only study whale and dolphin behavior through their sounds. But building reliable AI classifiers for underwater audio is tough. Data collection requires expensive specialized equipment, and according to the researchers, newly discovered sounds sometimes aren't linked to a specific species until decades after they're first recorded.

A team from Google Deepmind and Google Research now shows in a paper that a completely different approach might work better. Their general-purpose bioacoustic model Perch 2.0 was trained primarily on bird calls, yet it almost consistently outperforms every comparison model at classifying whale songs, including a Google model specifically trained on whales.

Bird model turns out to be better at recognizing whales

The 101.8 million-parameter Perch 2.0 model was trained on more than 1.5 million recordings of animal sounds covering at least 14,500 species. Most of these are birds, supplemented by insects, mammals, and amphibians. Underwater recordings are virtually absent from the training data. According to the paper, there are only about a dozen whale recordings, most of them captured with cell phones above water.

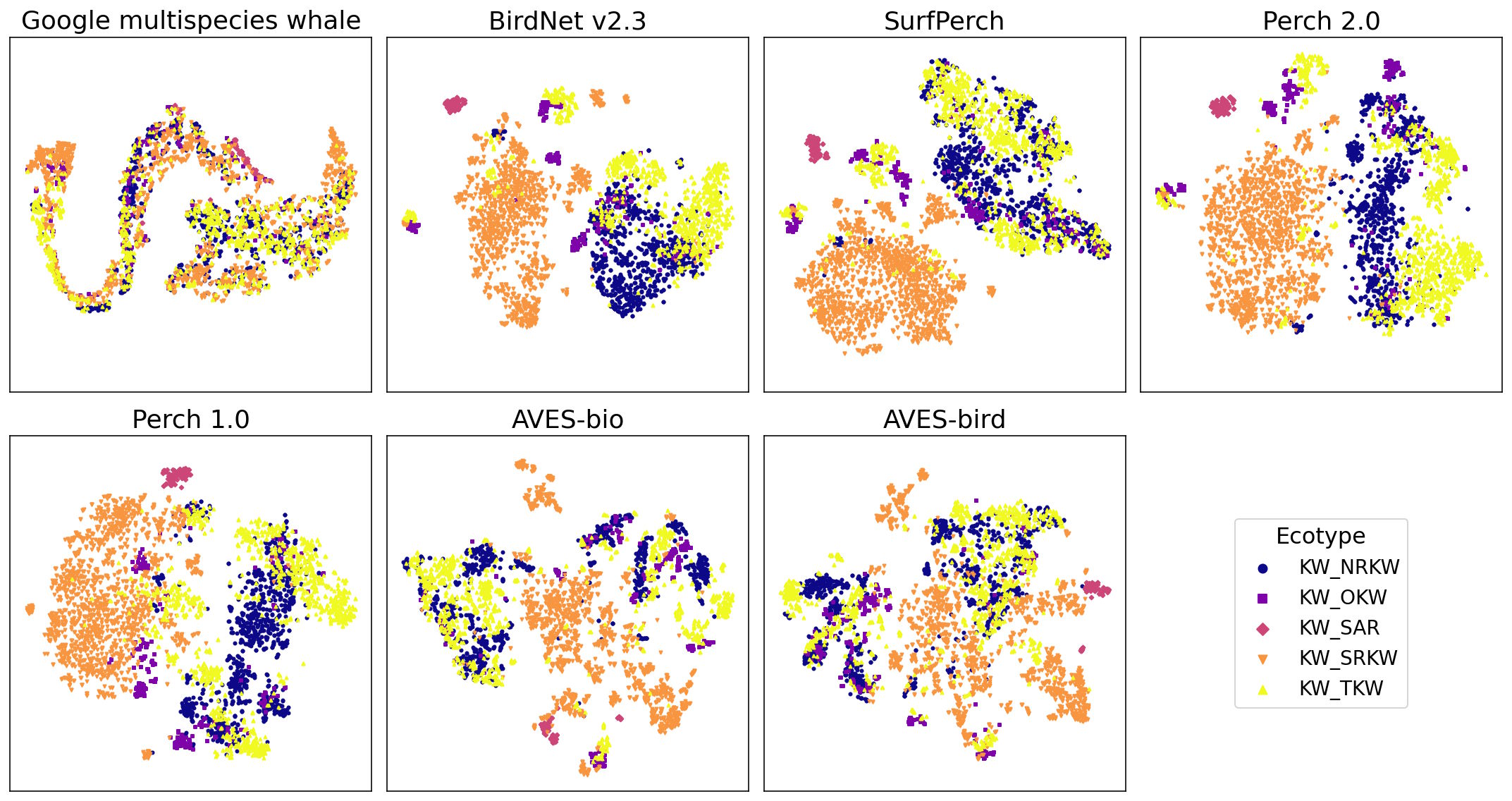

To test how well the bird model performs underwater, the researchers used three marine datasets. One contains various baleen whale species from the Pacific (NOAA PIPAN), another contains reef sounds like cracking and growling (ReefSet), and a third contains more than 200,000 annotated orca and humpback whale sounds (DCLDE 2026).

The model generates a compact numerical representation, called an embedding, for each recording. A simple classifier is then trained on these embeddings using just a few labeled examples, assigning sounds to the correct species.

Specialized whale AI falls behind general-purpose model

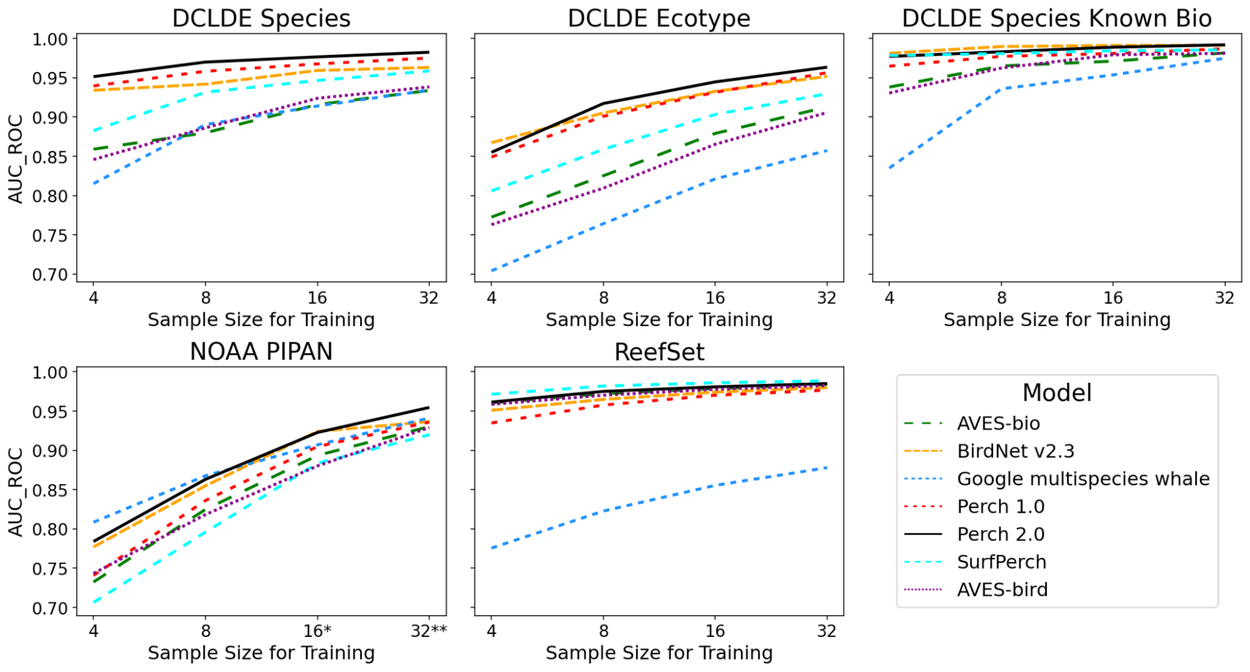

The researchers compared Perch 2.0 with six other models, including the Google Multispecies Whale Model (GMWM), which was specifically trained on whales. Performance was measured using the AUC-ROC score, a metric for classifier accuracy where 1.0 means perfect discrimination.

Perch 2.0 ranked first or second in almost every task. When distinguishing between different orca subpopulations by their sounds, it scored 0.945, while the whale model managed only 0.821. For classifying underwater sounds, Perch 2.0 hit 0.977 compared to the GMWM's 0.914, with only 16 training examples per category.

The gap gets even wider when the GMWM is used directly as a ready-made classifier instead of being fine-tuned through transfer learning. In that case, its performance drops to 0.612. The researchers suspect the model has overfit to specific microphones or other artifacts in its training data. Overall, specializing in a particular domain appears to limit a model's ability to generalize.

The "bittern lesson" of bioacoustics

The researchers offer three explanations for the surprising cross-domain transfer. First, neural scaling laws kick in: larger models with more training data generalize better, even to tasks outside their training domain.

Second, what the team calls the "bittern lesson," a play on the bird species bittern and the well-known "bitter lesson" in AI. Bird classification is particularly challenging because the differences between species are often minimal. North America alone has 14 species of pigeon, each with subtly different cooing sounds. A model that reliably picks up on these subtle differences learns acoustic features that turn out to be useful for completely different tasks.

Third, there's an evolutionary biology connection: birds and marine mammals independently developed similar sound production mechanisms, known as the myoelastic-aerodynamic mechanism. This shared physical basis could explain why acoustic features transfer so easily between animal groups.

Rapid classifiers for new discoveries in marine bioacoustics

The practical payoff lies in what's called "agile modeling." Passive acoustic data gets embedded in a vector database, and linear classifiers on pre-computed embeddings can be trained in just a few hours. That matters because new sounds are constantly turning up in marine bioacoustics. For example, the mysterious "biotwang" sound was only recently linked to Bryde's whales.

Google provides an end-to-end tutorial in Google Colab and makes the tools available on GitHub.

Google had already released its Multi-Species Whale Model in 2024, built to detect several whale species. Perch 2.0 followed in August 2025 as a broader bioacoustics foundation model.

AI News Without the Hype – Curated by Humans

As a THE DECODER subscriber, you get ad-free reading, our weekly AI newsletter, the exclusive "AI Radar" Frontier Report 6× per year, access to comments, and our complete archive.

Subscribe now