The EU’s AI Act pushes transparency but could overwhelm developers with paperwork

Can the EU’s strict new AI rules protect rights without smothering innovation? AI law expert Joerg Heidrich explores the risks of red tape overwhelming Europe’s tech sector.

The European Union wants its AI Act to become the global benchmark for artificial intelligence regulation. From Brussels' perspective, the law is designed to set an example for the rest of the world by prioritizing fundamental rights. This approach is a sharp contrast to the Trump administration's AI action plan, which focuses on cutting regulations and scaling back oversight.

The EU's blueprint for how the AI Act should work is detailed in the new "Code of Practice for General-Purpose AI Models". While technically voluntary, the code has significant legal implications for AI model providers, offering a path to comply with Articles 53 and 55 of the Act. The code splits providers into two groups: all must meet transparency and copyright requirements, while those whose models present systemic risks face tougher safety obligations. Companies that don't participate, like Meta, have to devise their own compliance strategies.

Documentation overload

The code confirms many of the criticisms aimed at the AI Act. In practice, it reads like a case study in overregulation - well-meaning but ultimately burdensome. Instead of supporting Europe's AI sector, it threatens to bury it under red tape and vague legal requirements.

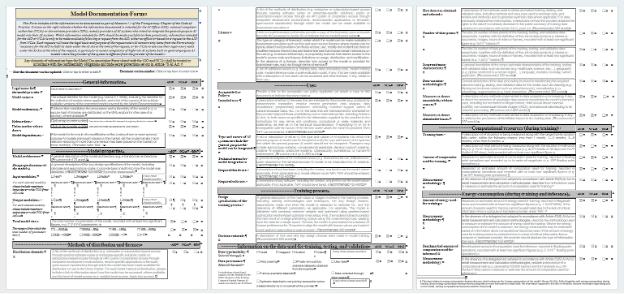

The code is split into three sections. The transparency section is supposed to give regulators and downstream providers a clear sense of how each AI system works. In reality, it acts as a tool for micromanagement, piling extra work onto developers. At the center is the "Model Documentation Form," a lengthy template every provider must fill out.

Digging into the details, many of the most demanding requirements - like exact parameter counts, training times, and compute usage - are only for the EU AI Office and national regulators.

Copyright lobby gets its way

The copyright section of the Code of Practice, which applies to all general-purpose AI models, tries to balance the need for vast training data with intellectual property rights. The result is a one-sided win for rights holders, while failing to provide legal certainty.

One sticking point is how rights holders can "opt out" of having their content used for AI training - an issue already being fought over in court. The code mentions the Robot Exclusion Protocol (robots.txt), but also says that "state of the art" and "widely used" technical measures are good enough. What that actually means remains unclear, and the courts will likely be sorting it out for years.

Unworkable output restrictions

A major challenge for AI providers is the requirement to use technical safeguards to prevent their models from reproducing copyrighted training material in an infringing manner. This ignores how modern AI works. Preventing a model from ever outputting fragments of its training data is extremely difficult, if not impossible, without crippling its capabilities. The rule puts a huge technical and legal burden on developers for outputs they ultimately can't control. The AI Act itself doesn't spell out this requirement.

Caught in a web of rules

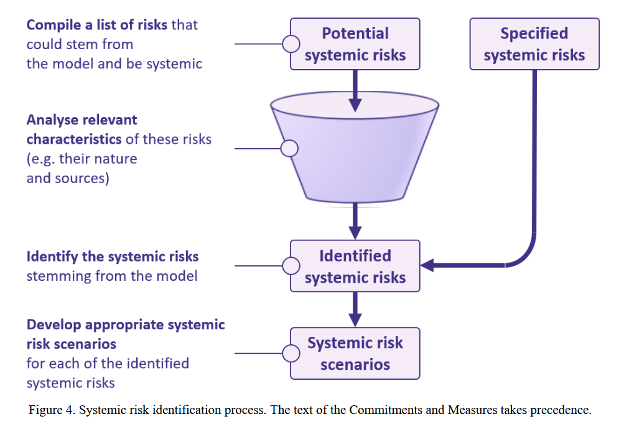

Things only get tougher in the section on safety and systemic risks, which targets providers of the most advanced AI models. It's unclear exactly which companies fall under this, but models from Anthropic, OpenAI, Google, X, and Meta are likely included, with Mistral representing Europe.

The 40-page "Safety and Security" chapter is the centerpiece of the EU's effort to control high-risk AI. The document outlines a maze of processes, paperwork, and vague definitions that would test even the largest U.S. tech firms with their armies of compliance staff. For startups and smaller companies, the requirements may be impossible to meet.

Any provider whose model is deemed to carry systemic risk has to create, implement, and constantly update a comprehensive "Safety and Security Framework." In practice, this means a sprawling set of procedures covering every phase of an AI system's life cycle. The likely result: development slows to a crawl as resources are tied up in compliance.

Outside evaluators add to the burden

Beyond internal requirements, the code calls for independent external evaluators to review AI models. This drives up costs, delays launches, and raises a basic question: where will enough highly qualified, truly independent experts come from? Notably, the AI Act itself doesn't require external evaluators.

Bureaucracy over innovation

A close look at the code makes the EU's dilemma clear. In trying to create safe, trustworthy AI, regulators have built a bureaucratic system that risks choking innovation. The balance between risk management and enabling progress is out of sync.

Europe is now caught between its push for "trustworthy AI" and the realities of global tech competition. While preventing harm and protecting rights is important, the regulatory overload - from exhaustive documentation to relentless risk monitoring and rigid ethics rules - could end up driving the most important AI innovation elsewhere.

AI News Without the Hype – Curated by Humans

As a THE DECODER subscriber, you get ad-free reading, our weekly AI newsletter, the exclusive "AI Radar" Frontier Report 6× per year, access to comments, and our complete archive.

Subscribe nowAI news without the hype

Curated by humans.

- Over 20 percent launch discount.

- Read without distractions – no Google ads.

- Access to comments and community discussions.

- Weekly AI newsletter.

- 6 times a year: “AI Radar” – deep dives on key AI topics.

- Up to 25 % off on KI Pro online events.

- Access to our full ten-year archive.

- Get the latest AI news from The Decoder.