AI reasoning models think harder on easy problems than hard ones, and researchers have a theory for why

Key Points

- Large reasoning models often show counterintuitive behavior, putting more computational effort into simple tasks than difficult ones while producing worse results overall.

- Researchers have established principles stating that reasoning effort should scale proportionally with task difficulty, and that accuracy should naturally decline as problems become more complex.

- A specialized training approach that better regulates the effort distribution across combined tasks can boost benchmark accuracy by up to 11.2 percentage points.

Large reasoning models often reach illogical conclusions: they think longer on simple tasks than difficult ones and produce worse results. Researchers have now proposed theoretical laws describing how AI models should ideally "think."

Reasoning models like OpenAI's o1 or Deepseek-R1 differ from conventional language models by going through an internal "thought process" before answering. The model generates a chain of intermediate steps—called a reasoning trace—before reaching a final solution. For the question "What is 17 × 24?", a trace might look like this:

I break the task down into smaller steps. 17 × 24 = 17 × (20 + 4) = 17 × 20 + 17 × 4. 17 × 20 = 340. 17 × 4 = 68. 340 + 68 = 408. The answer is 408.

This technique boosts performance on complex tasks like mathematical proofs or multi-step logic problems. But new research shows it doesn't always work efficiently.

Simple tasks trigger more thinking than complex ones

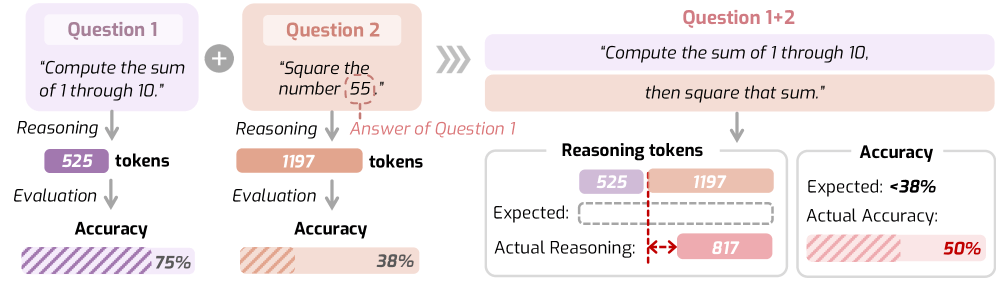

When Deepseek-R1 is asked to square a number, the model generates around 300 more reasoning tokens than for a compound task requiring both summing and squaring. At the same time, accuracy on the more complex task drops by 12.5 percent. A team of researchers from several US universities documented this behavior in a recent study.

This example points to a core problem with current large reasoning models: their reasoning behavior often doesn't follow any recognizable logic. Humans typically adjust their thinking effort to match task difficulty. AI models don't do this reliably—sometimes they overthink, sometimes they don't think enough. The researchers trace the problem to training data, since chain-of-thought examples are usually put together without explicit rules for thinking time.

New framework proposes laws for optimal AI thinking

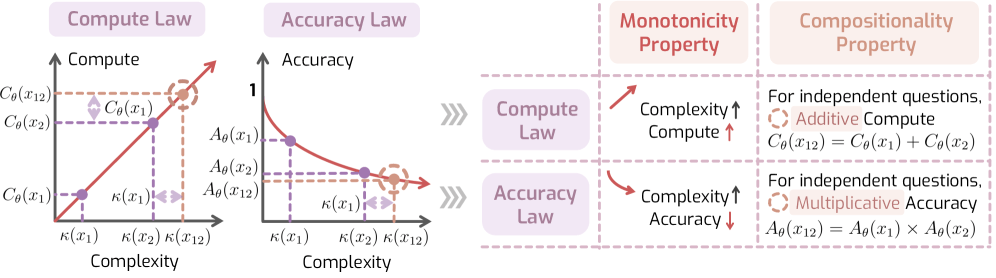

The proposed "Laws of Reasoning" (LoRe) framework lays out two central hypotheses. The first law says required thinking should scale proportionally with task difficulty; tasks twice as hard should need twice as much compute time. The second law says accuracy should drop exponentially as difficulty rises.

Since actual task difficulty can't be measured directly, the researchers rely on two testable properties. The first is simple: harder tasks should need more thinking time than easier ones. The second involves compound tasks: if a model requires one minute for task A and two minutes for task B, combining both should take about three minutes. Total effort should equal the sum of individual efforts.

Every tested model fails on compound tasks

The researchers built a two-part benchmark for their evaluation. The first part contains 40 tasks across math, science, language, and code, each with 30 variants of increasing difficulty. The second part combines 250 task pairs from the MATH500 dataset into composite questions.

Tests on ten large reasoning models paint a mixed picture. Most models handle the first property well, spending more thinking time on harder tasks. One exception is the smallest model tested, Deepseek-R1-Distill-Qwen-1.5B, which shows a negative correlation in language tasks: it actually thinks longer on simpler problems.

But every tested model fails on compound tasks. The gaps between expected and actual thinking effort were substantial. Even models with special mechanisms to control reasoning length, like Thinkless-1.5B or AdaptThink-7B, didn't perform any better.

Targeted training fixes inefficient thinking

The researchers developed a fine-tuning approach designed to promote additive behavior in compound tasks. The method uses groups of three: two subtasks and their combination. From several generated solutions, it picks the combination where thinking effort for the overall task best matches the sum of individual efforts.

With a 1.5B model, deviation in reasoning effort dropped by 40.5 percent. Reasoning skills improved across all six benchmarks tested. The 8B model saw an average five percentage point jump in accuracy.

One surprise: training on additive thinking times also improved traits that weren't trained directly. The researchers acknowledge some limitations: the benchmark only contains 40 initial tasks, and they didn't test proprietary models due to cost. The code and benchmarks are publicly available.

Industry doubles down on reasoning despite questions about its limits

In 2025, reasoning models have become central to the LLM landscape: from Deepseek R1 delivering competitive performance with fewer training resources to hybrid models like Claude Sonnet 3.7 that let users set flexible reasoning budgets.

At the same time, studies keep showing that while reasoning improves results, it's not the same as human thinking. Models likely just find existing solutions more efficiently within their trained knowledge. They likely can't 'think their way' to fundamentally new ideas the way humans can. Recent science benchmarks from OpenAI and other institutions support this view: models ace existing question-answer tests but struggle with complex, interconnected research tasks that need innovative solutions.

Still, the AI industry is betting big that reasoning models can be improved through massive compute increases. OpenAI, for example, used ten times as much reasoning compute for o3 as for its predecessor o1—just four months after its release.

AI News Without the Hype – Curated by Humans

As a THE DECODER subscriber, you get ad-free reading, our weekly AI newsletter, the exclusive "AI Radar" Frontier Report 6× per year, access to comments, and our complete archive.

Subscribe now