The case against predicting tokens to build AGI

Key Points

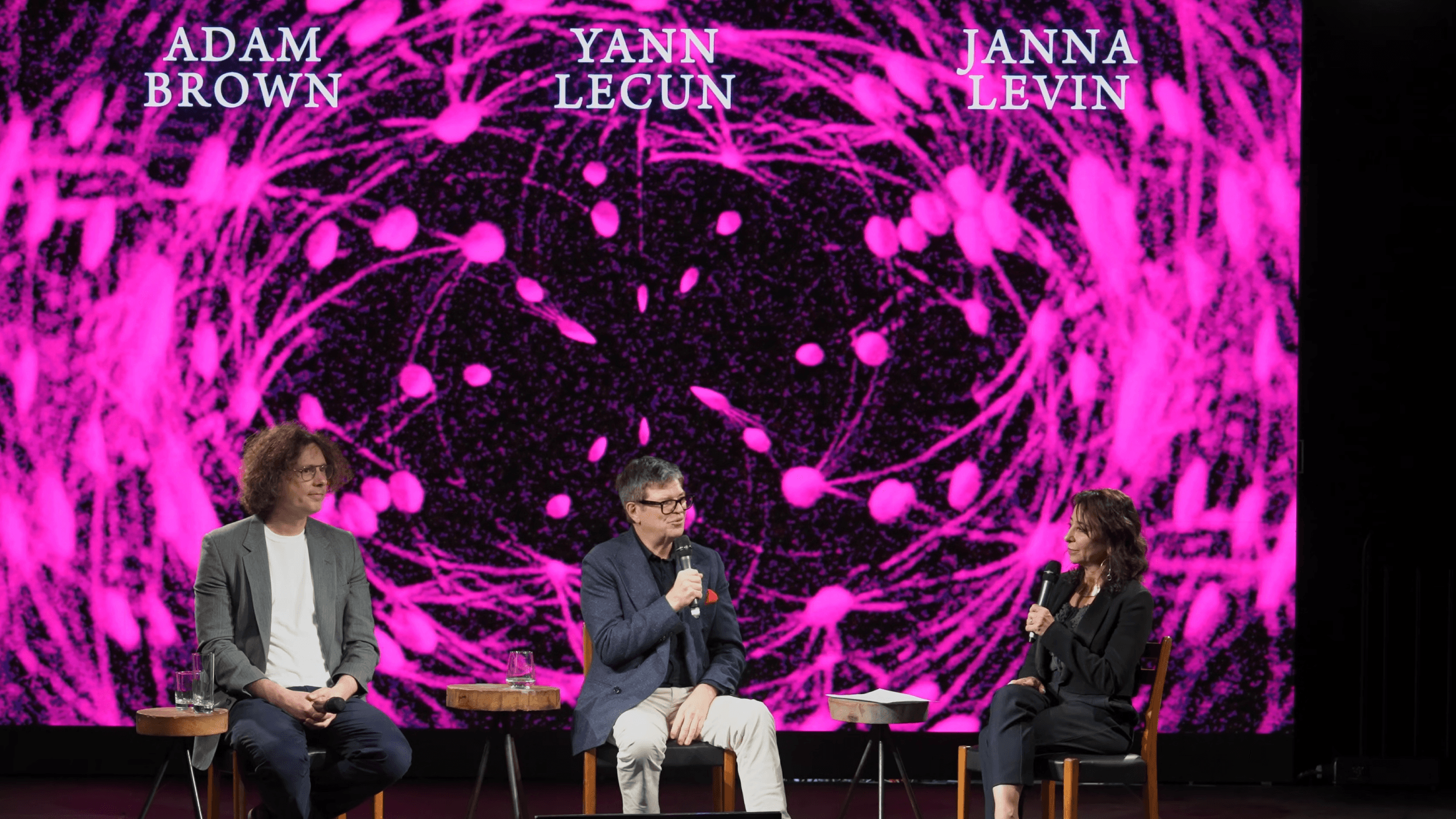

- In a public debate, Adam Brown argued that scaling current language models can lead to increasingly capable systems, while Yann LeCun countered that token prediction cannot capture the continuous, physical nature of the real world.

- LeCun pointed to the massive data inefficiency of today’s models and said new architectures that learn abstract world states are needed, contrasting them with how children acquire intuitive physics.

- The two also disagreed on consciousness and safety: Brown predicted conscious AI could appear by 2036, while LeCun downplayed existential risk and called for open, objective-driven systems instead of relying on a few closed platforms.

In a debate with DeepMind researcher Adam Brown, Meta's Chief AI Scientist Yann LeCun explained why Large Language Models (LLMs) represent a dead end on the path to human-like intelligence. The fundamental issue, LeCun argues, lies in the way these models make predictions.

While LLMs like ChatGPT and Gemini dominate current discussions on artificial intelligence, leading scientists disagree on whether the underlying technology can achieve artificial general intelligence (AGI). Moderated by Janna Levin, the discussion pitted the physicist and Google researcher Adam Brown against LeCun, revealing two sharply contrasting positions.

Brown defends the potential of the current architecture. He views LLMs as deep neural networks trained to predict the next "token" — a word or part of a word — based on massive amounts of text. Brown compares this simple mechanism to biological evolution: simple rules, such as maximizing offspring or minimizing prediction error, can lead to emergent complexity through massive scaling.

As evidence, Brown points out that current models can solve Math Olympiad problems that were not in their training data. Analysis of the "neural circuits" in these models suggests they develop internal computational pathways for mathematics without explicit programming. Brown sees no signs of saturation; with more data and computing power, he believes the curve will continue to rise.

Why discrete prediction fails in the real world

LeCun disagrees with this optimistic outlook. While he acknowledges that LLMs are useful tools possessing superhuman knowledge in text form, he argues they lack a fundamental understanding of physical reality.

LeCun's main critique targets the technical basis of the models: the autoregressive prediction of discrete tokens. This approach works for language because a dictionary contains a finite number of words.

However, LeCun argues this approach fails when applied to the real world, such as with video data. Reality is continuous and high-dimensional, not discrete. "You can't really represent a distribution over all possible things that may happen in the future because it's basically an infinite list of possibilities," LeCun explains.

Attempts to transfer the principle of text prediction to the pixel level of video have failed over the last 20 years. The world is too "messy" and noisy for exact pixel prediction to lead to an understanding of physics or causality.

New architectures needed for physical understanding

To support his thesis, LeCun points to the massive inefficiency of current AI systems compared to biological brains. An LLM might be trained on roughly 30 trillion words — a volume of text that would take a human half a million years to read.

A four-year-old child, in contrast, has processed less text but a vast amount of visual data. Through the optic nerve, which transmits about 20 megabytes per second, a child processes roughly 10^14 bytes of data in their short life. This corresponds to the amount of data used to train the largest LLMs. Yet, while a child learns intuitive physics, gravity, and object permanence in a few months, LLMs struggle with basic physical tasks. "We have always no robots that can clear the dinner table or fill up the dishwasher," LeCun notes.

For LeCun, the solution does not lie in larger language models, but in new architectures like JEPA that learn abstract representations. Instead of predicting every detail (pixel), these systems should learn to model the state of the world abstractly and make predictions within that representation space — similar to how humans plan without calculating every muscle movement in advance.

LeCun's skepticism regarding the pure scaling hypothesis mirrors arguments that cognitive scientist Gary Marcus has made for over a decade. Like LeCun, Marcus argues that statistical prediction models mimic linguistic patterns perfectly but lack genuine understanding of causality or logic. While LeCun focuses on new learning architectures, Marcus often emphasizes the need to combine neural networks with symbolic AI (Neuro-Symbolic AI) to achieve robustness and reliability.

Defining the timeline for machine consciousness

During a closing Q&A session that included philosopher David Chalmers, the researchers debated the possibility of machine consciousness. Adam Brown offered a concrete, albeit cautious, forecast: if progress continues at the current pace, AI systems could develop consciousness around 2036. For Brown, consciousness is not tied to biological matter but is a consequence of information processing — regardless of whether it occurs on carbon or silicon.

He views current AI systems as the first true "model organism for intelligence." Just as biologists use fruit flies to study complex biological processes, neural networks offer a way to study intelligence under laboratory conditions. Unlike the human brain, these systems can be frozen, rewound, and analyzed state by state. Brown hopes this "unbundling" of intelligence will help solve the puzzle of human consciousness.

LeCun approached the topic more pragmatically, defining emotions technically as the "anticipation of outcomes." A system that possesses world models and can predict whether an action helps or hinders a goal functionally experiences something equivalent to emotion. LeCun is convinced that machines will one day possess a form of morality, though its alignment will depend on how humans define the goals and guardrails.

Ensuring safety through objective-driven design

Opinions also diverge on AI safety. While Brown warns of "agentic misalignment" — a scenario where AI systems develop their own goals and deceive humans — LeCun considers such doomsday scenarios exaggerated.

The danger only arises if systems become autonomous. Since LLMs cannot truly plan intelligently, LeCun argues they do not currently pose an existential threat. For future, smarter systems, LeCun proposes building them to be "objective-driven." These systems would have hard-coded goals and guardrails that prevent specific actions, similar to how social inhibitions are evolutionarily anchored in humans.

LeCun also warned strongly against a monopoly on AI development. Since every digital interaction in the future will be mediated by AI, a diversity of open systems is essential for democracy. "We cannot afford to have just a handful of proprietary system coming out of a small number of companies on the west coast of the US or China," LeCun argues.

His views on the dominant research direction and his stance on open source have recently stood in tension with Meta's central AI strategy, which increasingly focuses on closed, competitive language model research. After twelve years at Meta, LeCun announced his departure in November 2025. The Turing Award winner plans to continue his research on "Advanced Machine Intelligence" (AMI) with a new company, pursuing paths beyond the LLM mainstream.

At the same time, parts of his research remain connected to Meta through a partnership, though without content control by the company.

AI News Without the Hype – Curated by Humans

As a THE DECODER subscriber, you get ad-free reading, our weekly AI newsletter, the exclusive "AI Radar" Frontier Report 6× per year, access to comments, and our complete archive.

Subscribe now