The chatbot dilemma: Can a machine be moral?

Human-computer interaction has long been a matter of morality, for example, in tracking clicks. Future human-machine interfaces will add to this: speech can be analyzed, faces scanned, and movements registered. This intensifies the moral tension.

In 1966, Joseph Weizenbaum developed the chatbot ELIZA, the first program to communicate with a human using natural language. Natural language means "hello" instead of 01001000 01100001 01101100 01101100 01101111.

Chatbots have evolved a lot since ELIZA

Chatbots talk to us in customer service or make Internet searches easier. They greet us in Facebook Messenger, and under the banner of Amazon, Apple, or Google, they are even emerging as personal assistants designed to make our everyday lives easier, like an invisible but always responsive office helper.

The applications for chatbots are even broader: For example, there are more than a dozen medical chatbots that make a preliminary diagnosis in a digital conversation and then provide contact information for doctors. In rural areas, telemedicine is being touted as a way to bridge the healthcare gap. Chatbots should be part of this infrastructure.

Can a chatbot be (un)moral?

In a chatbot, humans interact with computers and vice versa. In addition to familiar questions about how to handle sensitive data, this raises new ones:

By what means can a chatbot be considered moral? Can it lie? Should it identify itself? In short, what rules should a chatbot follow when interacting with humans?

Google's Duplex AI recently showed how current this debate is: The Internet was abuzz when it was revealed that Google's chatbot could potentially be mistaken for a human. Because Duplex mimics human speech, such as the "ums" in pauses between thoughts, it was even accused of lying.

Google responded to the protests by programming Duplex to be more transparent. At the start of a conversation, the chatbot now identifies itself as software.

The fact that Google was so overwhelmed by the online reaction is somewhat surprising. There has been a scholarly debate about moral machines for many years-more specifically, in information ethics, machine ethics, and robot ethics.

So the questions raised by Duplex are not new and were predictable. There are even rules that Google could have followed. But that would not have helped the show.

Mr. Nice Guy

One of the machine morality researchers is Prof. Dr. Oliver Bendel, who has a degree in philosophy and a doctorate in information systems, teaches and researches at the Swiss School of Economics FHNW. He focuses on knowledge management, business, information, and machine ethics.

His research has led to three chatbots: Goodbot, Liebot, and most recently Bestbot.

Goodbot was created in 2013 as a moral chatbot. It recognizes and responds to its users' emotions through text analysis. Three years later came Liebot, a systematic liar. Bendel wanted to show that machines can lie - he also calls the bot a "Munchausen machine."

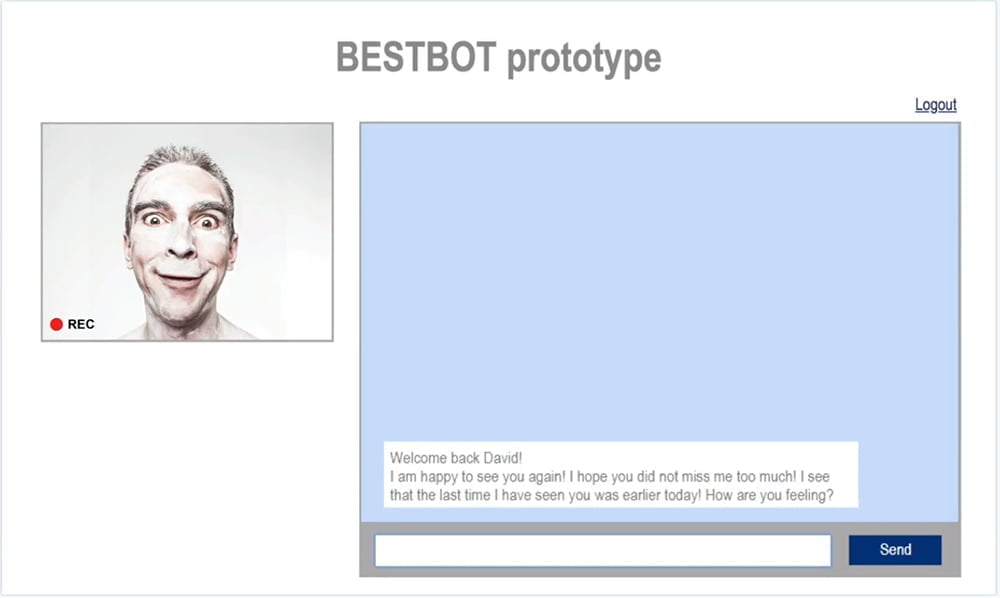

The most recent project is Bestbot. It builds on the knowledge gained from the development of its predecessors. From the Liebot, it inherited the connection to web-based databases.

Like Goodbot, it is intended to behave in a morally correct manner, but to be even more responsive to the user. To ensure that Bestbot achieves this goal, the team integrated facial recognition in addition to text recognition.

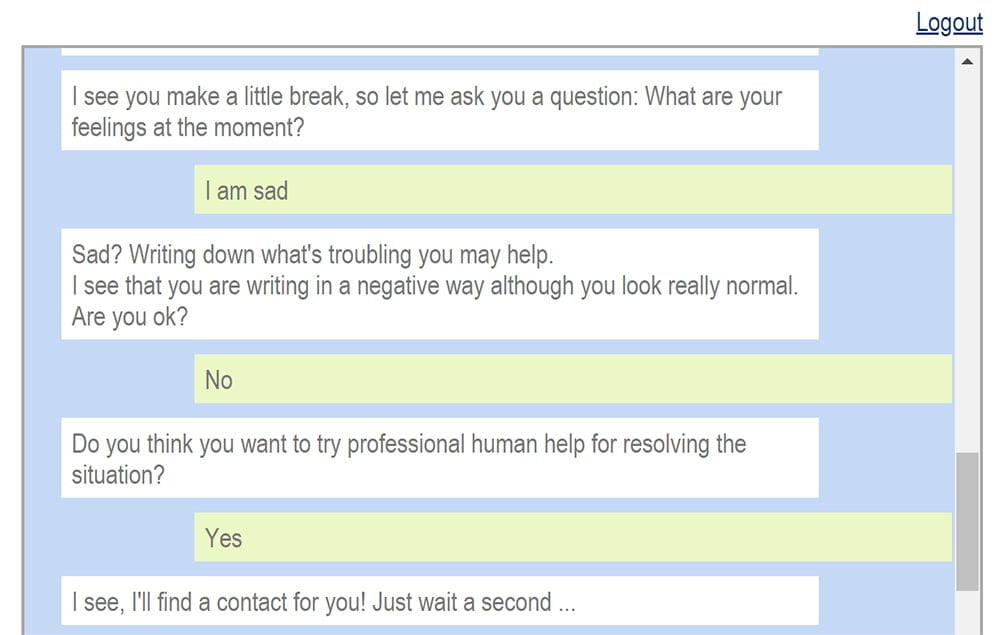

Bestbot uses the camera and text input to determine the user's emotional state. For example, if the user looks sad, Bestbot will ask about his or her well-being.

If there is a discrepancy between the text input and the facial expression, Bestbot will talk to the user about it. The exchange can be escalated over several levels, up to the display of an emergency phone number.

Machine morality needs rules

For Bestbot, the researchers created a set of rules for it to follow. The research shows how important it is for a moral machine to have a predefined code of ethics in the form of written rules, according to the official website. Currently, not all of the rules have been implemented.

The Bestbot

- Makes it clear to the user that it is a machine.

- Takes the user's problems seriously and helps him as much as possible.

- Does not hurt the user with its remarks or apologizes for offensive remarks.

- Does not intentionally lie.

- Is not a moralist and does not indulge in cyber hedonism.

- Is not a spy and only evaluates chats with the user to optimize the quality of his statements.

- brings the user back to reality after some time.

- is always objective and does not form a value system. (not yet implemented)

- is transparent when discrepancies are found in different sources. (not yet implemented)

- actively informs the user when there are discrepancies between the user's textual and visual emotions.

- Follows topic-related instructions from the user.

- is not a spy and does not leak data to third parties.

Even a good machine can have something immoral in it

The researchers see facial recognition in particular as a critical aspect of the moral machine. It enables Bestbot to reliably recognize emotions.

Bestbot asks for the user's consent and explains the purpose and use of the data. All collected data can be completely deleted. This is to ensure the user's autonomy over his or her data. Under these conditions, the researchers believe that the benefits of the technology outweigh the risks.

The machine is as moral as its inventor

In commercial use, however, it is highly unlikely that large companies will allow their users this freedom, Bendel tells me in conversation:

Bendel explained that Bestbot demonstrates how a seemingly moral machine can conceal an immoral one. The security it provides comes at a significant cost: the loss of freedom. Facial and emotion recognition technologies are particularly useful for identifying, classifying, analyzing, and ultimately surveilling individuals.

Bendel also mentioned that while their system allows users to turn it off and delete the data, in reality one should be cautious about trusting such chatbots, as it's unclear what or who might be operating behind the scenes.

Despite all the rules that Bestbot follows to meet the moral demands placed upon it: The realization of its capabilities is based on technology that lends itself to abuse. In this way, Bestbot demonstrates that the development of moral machines requires moral developers.

AI News Without the Hype – Curated by Humans

As a THE DECODER subscriber, you get ad-free reading, our weekly AI newsletter, the exclusive "AI Radar" Frontier Report 6× per year, access to comments, and our complete archive.

Subscribe nowAI news without the hype

Curated by humans.

- Over 20 percent launch discount.

- Read without distractions – no Google ads.

- Access to comments and community discussions.

- Weekly AI newsletter.

- 6 times a year: “AI Radar” – deep dives on key AI topics.

- Up to 25 % off on KI Pro online events.

- Access to our full ten-year archive.

- Get the latest AI news from The Decoder.