The ARC benchmark's fall marks another casualty of relentless AI optimization

Update from December 25, 2025:

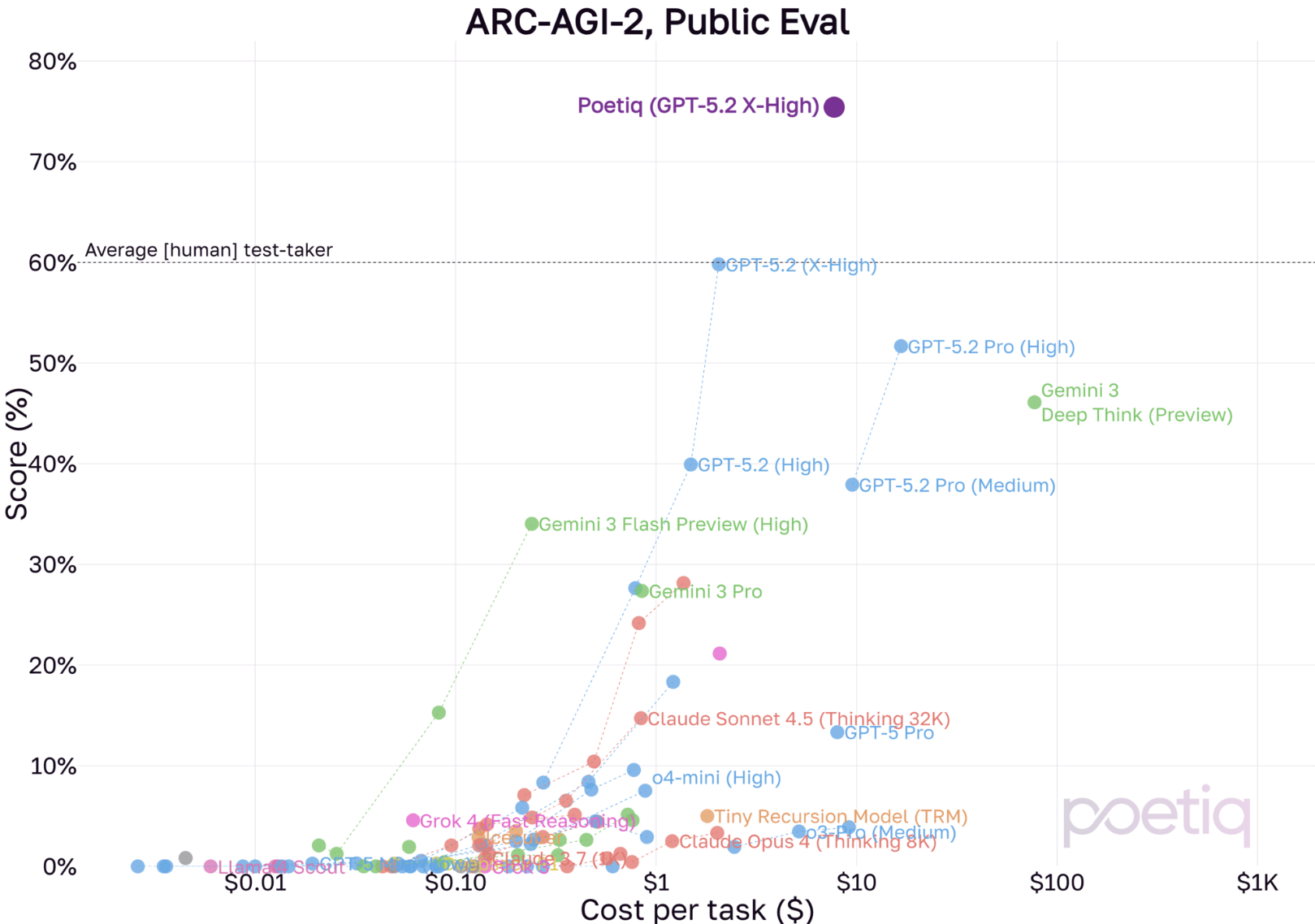

Poetiq has raised the bar even higher on the ARC-AGI-2 benchmark. The AI startup achieved a 75 percent accuracy rate on the public test dataset using OpenAI's GPT-5.2 X-High. That's roughly 15 percentage points above the previous best score (see below) and well beyond human level performance. The cost came in under $8 per task, significantly cheaper than before.

Poetiq says the X-High variant is likely cheaper per task than the High variant because the model reaches correct answers faster. Achieving this result required tweaks to both the prompt and the code, what the company calls the "reasoning strategy." The company plans to release the code soon.

Poetiq emphasizes that GPT-5.2 didn't receive any special training or model-specific adjustments. The company calls it a remarkable improvement in a short time, both in accuracy and cost compared to earlier models. If the pattern from previous tests holds, GPT-5.2 X-High with the Poetiq system could also perform significantly better than all previous configurations on the ARC Prize's official semi-private tests.

When one observer pointed out that the approach is specific to ARC-AGI and may not transfer to real world applications, Poetiq responded that while the ARC-AGI solver is specialized, the broader Poetiq meta system behind it is designed for general use.

The Poetiq solver guides the underlying model (GPT-5.2 in this case) to write code that solves each individual task. The system then runs the code, checks it for correctness, and fixes any errors. Multiple independent runs are combined to improve the reliability of the final results.

Original article from November 29:

For years, the ARC benchmark was considered a nearly insurmountable obstacle for AI systems, a true test of fluid intelligence rather than simple memorization. But new results show that even this barrier is crumbling under the relentless optimization machinery of modern AI labs.

The "Abstraction and Reasoning Corpus"—later renamed ARC-AGI—was originally designed to separate true learning from statistical parroting. Now, it faces the same fate as many benchmarks before it: newer methods are simply overpowering it.

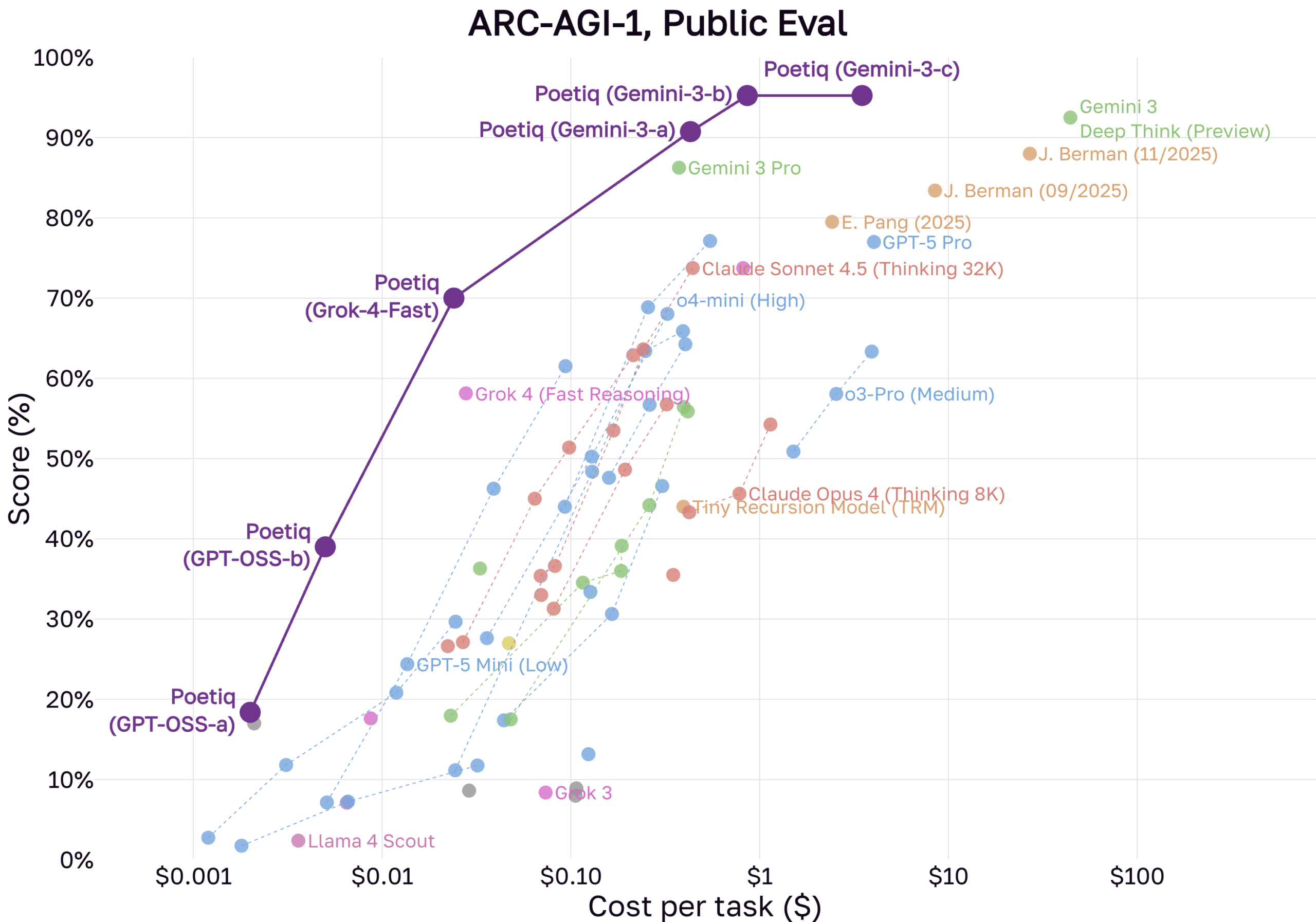

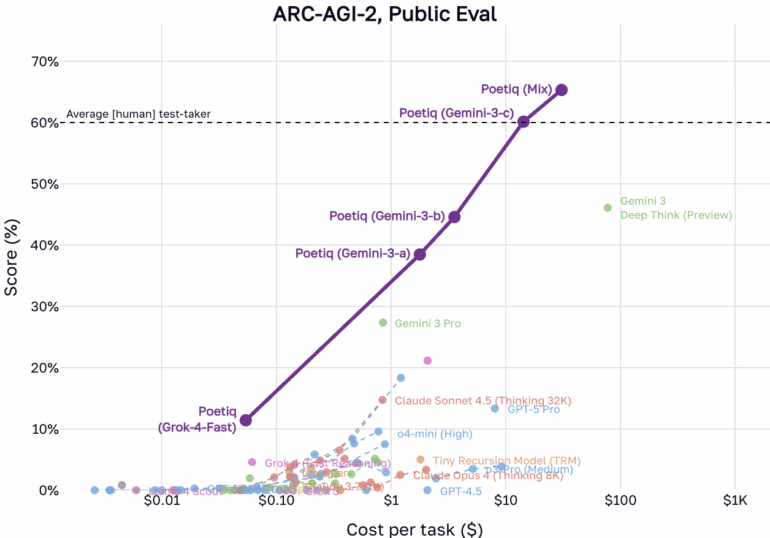

New results from AI company Poetiq suggest the original ARC-AGI-1 benchmark is effectively solved. In a recent announcement, the company claims its systems, built on models like OpenAI's and Google's, have maxed out performance on the first dataset. More notably, the system reportedly beat the human average of 60 percent on the significantly harder ARC-AGI-2 dataset.

Poetiq’s approach combines advanced language models, including Gemini 3 and GPT-5.1, with open-source models integrated into a custom architecture. According to Poetiq, the system operates in an iterative loop: it generates proposed solutions, evaluates feedback, and refines answers through a self-audit before finalizing the result.

Specialized models turn abstraction into an optimization problem

When AI researcher and Keras creator François Chollet introduced ARC in 2019, he pitched it as an antidote to the deep learning paradigm. The goal was to measure "skill acquisition efficiency"—how well a system learns new tasks—rather than how much data it could memorize.

Researchers struggled with these colorful grid puzzles for years. While language models crushed other benchmarks, ARC success rates remained low. For some, it became the "North Star" of AGI research; for others, it highlighted the limitations of scaling large models.

That dynamic shifted with the arrival of specialized reasoning models and techniques like Test-Time Training (TTT). A major turning point occurred in December 2024, when OpenAI's o3-preview suddenly scored over 75 percent on ARC-AGI-1. What began as a test of human-like abstraction is fast becoming an optimization target for reinforcement learning and search algorithms. Labs are now tuning their systems to master ARC's specific logic.

Efficiency is improving alongside performance. According to Poetiq, its "Poetiq (GPT-OSS-b)" system, based on the open model GPT-OSS-120B, achieves over 40 percent accuracy on ARC-AGI-1 for less than a cent per task. The era of ARC solutions requiring massive compute appears to be ending, a trend further supported by the non-LLM "Tiny Recursive Model."

Performance drops suggest models are still memorizing public data

These high scores currently apply only to "public" datasets, not the "semi-private" sets held back by ARC administrators. In its own analysis, Poetiq notes that many underlying LLMs perform significantly worse when switching from public evaluation sets to semi-private ones.

The culprit is likely "data contamination": public benchmarks often end up in the training data for large models. True generalization is only proven on tasks a model has definitely never seen. Poetiq expects its own systems to see a similar performance dip on ARC-AGI-1 for this reason.

However, the newer ARC-AGI-2 might be more resistant to this effect. Poetiq describes the sets as "more tightly calibrated" and claims its system was never trained on ARC-AGI-2 tasks, although the foundation models it uses, might be.

The industry shifts focus toward test-time adaptation

Chollet has watched this evolution closely. He views recent successes as evidence of a fundamental strategic shift in AI development.

Describing results from reasoning models like o3 as a "a surprising and important step-function increase in AI capabilities," Chollet argues that the old strategy of scaling intelligence via larger models and more data is hitting a wall with tasks like ARC. Instead, the field has entered the era of test-time adaptation.

Models are no longer static responders. They adapt at runtime, using techniques similar to program synthesis and chain-of-thought reasoning to reconfigure themselves for specific problems. For Chollet, this validates his theory that intelligence is a process of adaptation, not a static knowledge warehouse.

He maintains that solving ARC is a necessary step toward AGI, but not AGI itself. Current models still fail basic tasks and lack a profound understanding of the world. The benchmark's purpose was to push research toward better systems. And it worked.

The industry responded, though perhaps more pragmatically than cognitive scientists hoped. Instead of "general intelligence," we got specialized reasoning machines that tackle puzzles through iterative loops and code generation.

With ARC-AGI-1 effectively saturated, even the tougher ARC-AGI-2 is now falling. Poetiq's system beat the human average despite never training on those specific tasks.

Solving the benchmark proves its value as a catalyst

ARC-AGI is experiencing the typical lifecycle of a benchmark: it becomes a metric for marketing departments. Once a target is defined and incentives exist, like the ARC Prize's million-dollar purse, labs will optimize until they hit the number.

This doesn't mean AI is thinking like a human. It demonstrates the adaptability of modern AI research, which can hit almost any abstract target by combining compute, synthetic data, and sophisticated search methods.

ARC-AGI-1 and ARC-AGI-2 succeeded by forcing a focus on reasoning and adaptation. That they are now being "solved" isn't a failure of the test but proof of its effectiveness in driving development. It remains to be seen whether these methods lead to true fluid intelligence. Many people, including Chollet, believe that something is still missing.

He is already looking ahead to ARC-AGI-3, which will use interactive environments to test model "agency"—the ability to act.

Poetiq has released its code and results on GitHub.

AI News Without the Hype – Curated by Humans

As a THE DECODER subscriber, you get ad-free reading, our weekly AI newsletter, the exclusive "AI Radar" Frontier Report 6× per year, access to comments, and our complete archive.

Subscribe nowAI news without the hype

Curated by humans.

- Over 20 percent launch discount.

- Read without distractions – no Google ads.

- Access to comments and community discussions.

- Weekly AI newsletter.

- 6 times a year: “AI Radar” – deep dives on key AI topics.

- Up to 25 % off on KI Pro online events.

- Access to our full ten-year archive.

- Get the latest AI news from The Decoder.