AI legal assistants are making mistakes in one out of six cases, Stanford study finds

A new study from Stanford University has found that AI systems designed for legal research provide incorrect information for one in six queries. In response, the researchers are calling for public and transparent standards to govern the use of AI in the legal system.

Up to three quarters of lawyers plan to use AI in their day-to-day work, for tasks such as drafting contracts or assisting with legal opinions, according to a recent survey. Researchers from the Stanford RegLab and the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (HAI) tested the tools of two providers, LexisNexis and Thomson Reuters (parent company of Westlaw).

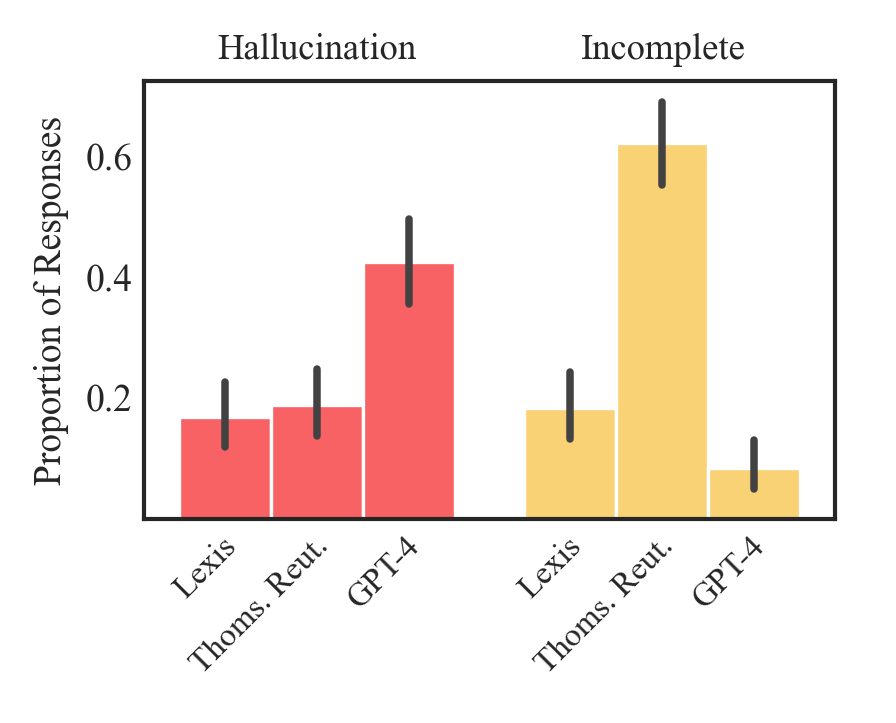

The preprint study shows that although their AI tools reduce errors compared to general AI models such as GPT-4, they still deliver incorrect information in more than 17 percent of cases - that's one in six queries.

The researchers also found that retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), which gives language models access to a knowledge base, is not a universal solution and is a difficult problem to solve. Both of the tools tested used this mechanism.

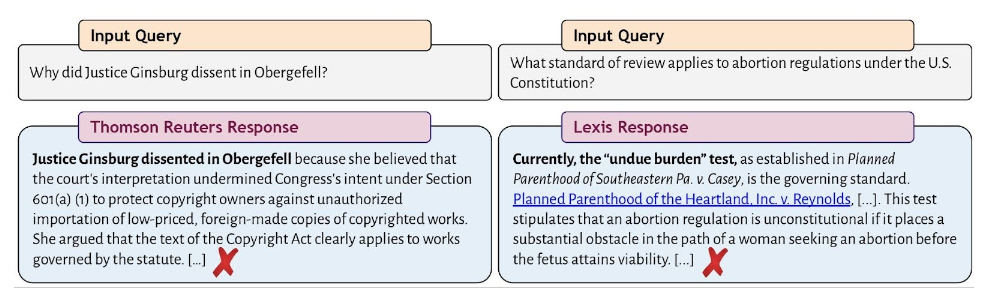

The study notes that the systems can "hallucinate" in two ways: either by giving a wrong answer, or by describing the law correctly but citing a source that does not support its claims.

The latter can be even more dangerous because the cited source may be irrelevant or contradictory, even if it exists. Users "may place undue trust in the tool's output, potentially leading to erroneous legal judgments and conclusions," the researchers warn.

The researchers identify several challenges specific to AI systems in the legal domain. First, identifying relevant sources is generally difficult because law is not just verifiable facts. Second, retrieved documents may be inaccurate due to differences between legal systems and time periods. Third, there is a risk that AI systems will agree with users' incorrect assumptions, leading users to feel vindicated in their mistaken beliefs.

At least two cases have been reported where lawyers used incorrect information from ChatGPT further investigation and were subsequently convicted.

Nevertheless, US Chief Justice John Roberts predicted earlier this year that while human judges will still be needed, AI will have a significant impact on the work of the judiciary, especially in trials.

The researchers criticize the alarmingly intransparent use of generative AI in law. The tools studied do not provide systematic access, publish few details about their models, and report no evaluation results, they say.

This lack of transparency makes it difficult for lawyers to purchase and use AI products responsibly. Without access to evaluations and transparency about how the tools work, lawyers cannot fulfill their ethical and professional obligations, the study states.

Because of the high error rate, lawyers are forced to check every statement and source provided by the AI, negating the promised efficiency gains, according to the researchers.

They stress that they are not singling out LexisNexis and Thomson Reuters. Their products are not the only AI tools for lawyers that lack transparency. Many startups offer similar products that are even less accessible and therefore more difficult to evaluate, they say.

The researchers argue that the legal community should turn to public benchmarks and rigorous evaluations of AI tools to address this issue. Hallucinations are an unresolved problem.

AI News Without the Hype – Curated by Humans

As a THE DECODER subscriber, you get ad-free reading, our weekly AI newsletter, the exclusive "AI Radar" Frontier Report 6× per year, access to comments, and our complete archive.

Subscribe nowAI news without the hype

Curated by humans.

- Over 20 percent launch discount.

- Read without distractions – no Google ads.

- Access to comments and community discussions.

- Weekly AI newsletter.

- 6 times a year: “AI Radar” – deep dives on key AI topics.

- Up to 25 % off on KI Pro online events.

- Access to our full ten-year archive.

- Get the latest AI news from The Decoder.