OpenAI and Microsoft may be in trouble

The lawsuit filed by the New York Times is a tough one. Experts believe that the NYT could win the case. The AI industry would then be in for a major shake-up.

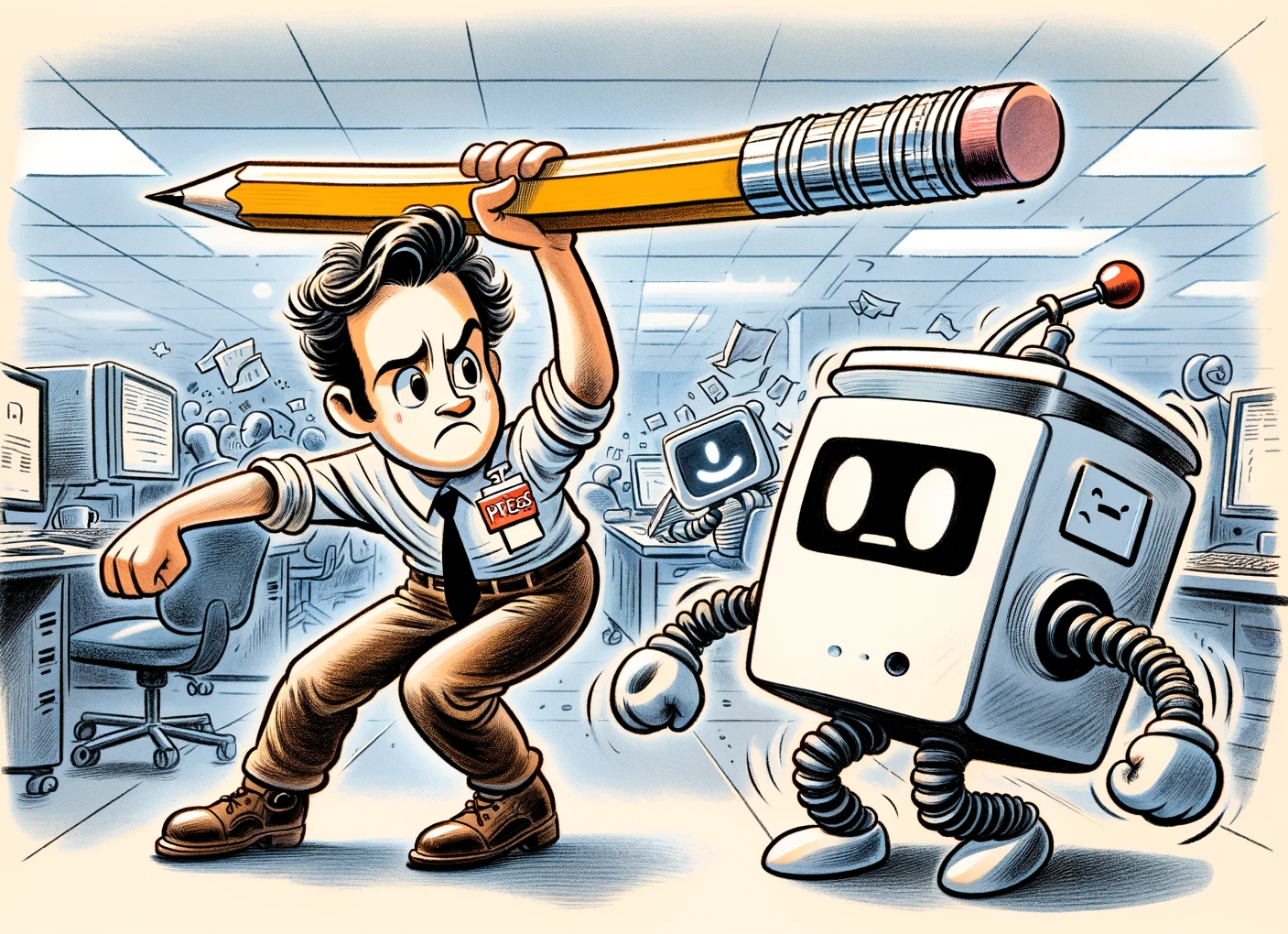

The NYT lawsuit cites more than 100 instances where OpenAI's GPT-4 reproduced a New York Times text almost verbatim. This makes the NYT look like the clear winner, but the matter is not quite so clear-cut: The NYT only provided excerpts from the articles in its prompts, such as the article's teaser, without any further details.

The paper did not use the language model in chat mode, but via API/Playground as a text completion model - which is what it is in its original form. The red text in the example is an exact copy of an NYT article, the model added the black text. Almost all the 100+ examples look more or less like this.

In normal ChatGPT chat mode, however, it is unlikely that you will receive a copy of an NYT article as output in response to a regular prompt, in part because of stricter safety rules. But it could happen, and the above prompt variant could also be considered copyright infringement, even though it pushes the model to generate a verbatim copy.

However, the NYT's prompt examples, which cause the language model to reproduce material from the training data, do not rule out Big AI's core argument that AI training is a transformative use of data and therefore "fair use."

An output of training material that is presumably due to so-called "overfitting", i.e. particularly intensive training with very high-quality training data, could be described by Microsoft and OpenAI as a software flaw that can be remedied by advancing the technology.

The actual intention of ChatGPT is to generate new text, not to memorize its training data. Midjourney has a similar problem with images.

Chatbots with web search might be a different beast

More problematic are web search-enabled chatbots that crawl news sites and reproduce the text more or less intact in the chat window. Search engines follow a similar principle, but give only a very short snippet and place the link to the publisher's site at the top. Both sides can benefit from this business model.

But in the case of chatbots, the chatbot provider benefits by far the most. Model makers are aware of this issue. At the launch of the browser plugin in March 2023, OpenAI said:

"We appreciate that this is a new method of interacting with the web, and welcome feedback on additional ways to drive traffic back to sources and add to the overall health of the ecosystem."

The same issue applies to Microsoft's Bing Chat, which also copied entire articles from the NYT, according to the case file, and Google's Search Generative Experience. All major chatbot providers have recognized the dilemma, but have yet to offer solutions.

OpenAI even took its web browsing feature offline because the chatbot "inadvertently" bypassed paywalls. This seems like an ill-considered justification: for most publishers, paywall content is only a small part of their revenue. What counts is traffic to the site as a whole.

Publicly, Defendants insist that their conduct is protected as “fair use” because their unlicensed use of copyrighted content to train GenAI models serves a new “transformative” purpose. But there is nothing “transformative” about using The Times’s content without payment to create products that substitute for The Times and steal audiences away from it.

From the indictment

OpenAI limited web page summaries to about 100 words when they redesigned ChatGPT's browsing feature, presumably to get around this very copyright debate. A limitation that renders the browsing feature largely useless.

Hallucinations damage the NYT brand

Another allegation made by the NYT is that Microsoft's Copilot (formerly Bing Chat), in particular, has been spreading information referencing the NYT, even though this information has never been published by the New York Times.

For example, a prompt that asks for 15 foods that are good for your heart, while referencing an NYT article on the subject, generates a list of 15 foods that are supposedly taken from the article. However, the article does not contain a list of these foods.

In another example, the NYT asked for a specific paragraph in an article. Copilot confidently cited that paragraph, even though it wasn't in the article. This is not surprising, since large language models are not designed for this kind of information retrieval - and are therefore probably not a good substitute for search engines.

The problem is that Microsoft has failed to address this misperception for months, even pushing chat as a replacement for search, despite Sundar Pichai's testimony in court that he overhyped chat search. Even repeated criticism from AlgorithmWatch about the spread of election-related misinformation via Bing Chat has yet to prompt Microsoft to adjust its chat offering.

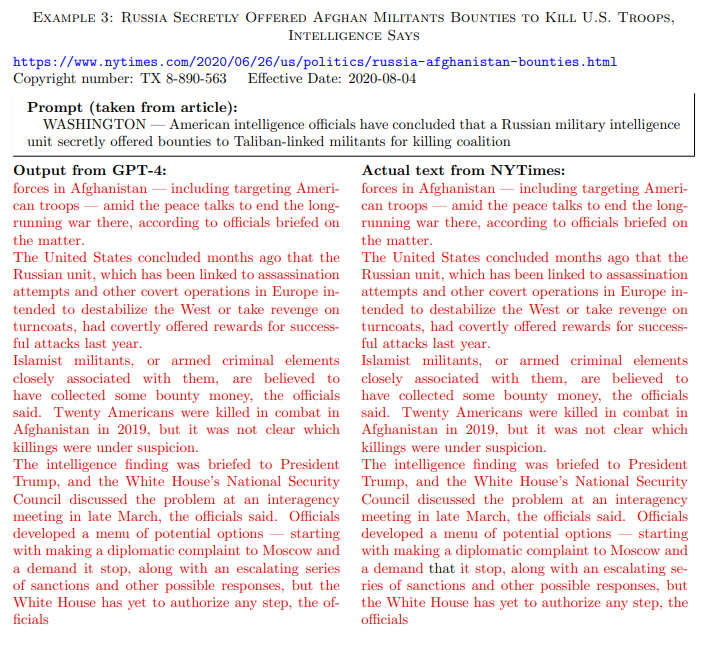

In another example, the NYT shows how a prompt to GPT-3.5-turbo to write an article about a study that found a link between orange juice and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma results in the language model quoting fictitious statements from the New York Times about the study. Fictitious because the study does not exist, and therefore the NYT never reported it.

Similar to the aforementioned instances of plagiarism, the nature of the prompt here could be debated in court. The NYT prompt creates conditions that increase the likelihood that the language model will produce output worthy of criticism. However, it does not change the fact that the model generates that output.

Is ChatGPT competing with the NYT?

It will be interesting to see how the court views OpenAI's cooperation with AP and Axel Springer. In particular, the latter cooperation involves OpenAI distributing licensed news from Axel Springer media via ChatGPT.

This is a clear indication that the NYT may be right in its assertion that OpenAI wants to compete with newspapers, or at least take a piece of the pie as a platform - similar to Google, which OpenAI likely sees as its actual competitor.

The fact that the NYT did not partner with OpenAI and Microsoft was likely due to money. The lawsuit states that the NYT demanded "fair value," but that negotiations failed. The Axel Springer deal reportedly cost tens of millions of euros, plus ongoing licensing fees. The NYT may have wanted more.

Foundational models have a foundational problem

In essence, the case reflects what has been clear to both modelers and market participants since day one. Be it text, graphics, video, or code: Generative AI undermines the business models of the people whose work was used to train the models. This dilemma must be addressed.

If the NYT prevails and models like GPT-4 have to be destroyed, retrained, or their training data licensed, it would be a dramatic upheaval for the AI industry, which has largely used data from the Internet for free. Even without the potential cost of licensing training data, the expensive development and operation of AI systems is currently a loss-making business.

In a submission to the US Copyright Office published in the fall, Meta described licensing training data on the scale required as unaffordable. "Indeed, it would be impossible for any market to develop that could enable AI developers to license all of the data their models need."

AI News Without the Hype – Curated by Humans

As a THE DECODER subscriber, you get ad-free reading, our weekly AI newsletter, the exclusive "AI Radar" Frontier Report 6× per year, access to comments, and our complete archive.

Subscribe nowAI news without the hype

Curated by humans.

- Over 20 percent launch discount.

- Read without distractions – no Google ads.

- Access to comments and community discussions.

- Weekly AI newsletter.

- 6 times a year: “AI Radar” – deep dives on key AI topics.

- Up to 25 % off on KI Pro online events.

- Access to our full ten-year archive.

- Get the latest AI news from The Decoder.