Scientific AI models trained on different data are learning the same internal picture of matter, study finds

MIT researchers compared 59 scientific AI models and found they converge to similar internal representations of molecules, materials, and proteins, even when built on different architectures and trained on different tasks.

Scientific AI models work with vastly different inputs. Some receive molecules as coded strings, others process 3D atomic coordinates, and still others work with protein sequences. Yet despite training on completely different data, they appear to learn something similar under the hood. That's the finding of a new study from researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The team, led by Sathya Edamadaka and Soojung Yang, examined 59 different models. These included specialized systems for molecules, materials, and proteins, as well as large language models like DeepSeek and Qwen. The researchers extracted each model's internal representations and compared them using several metrics.

Higher performance correlates with stronger convergence

The learned representations line up significantly across input formats. Models working with 3D coordinates show strong agreement with each other, as do text-based models. More surprisingly, clear similarities exist between these groups as well.

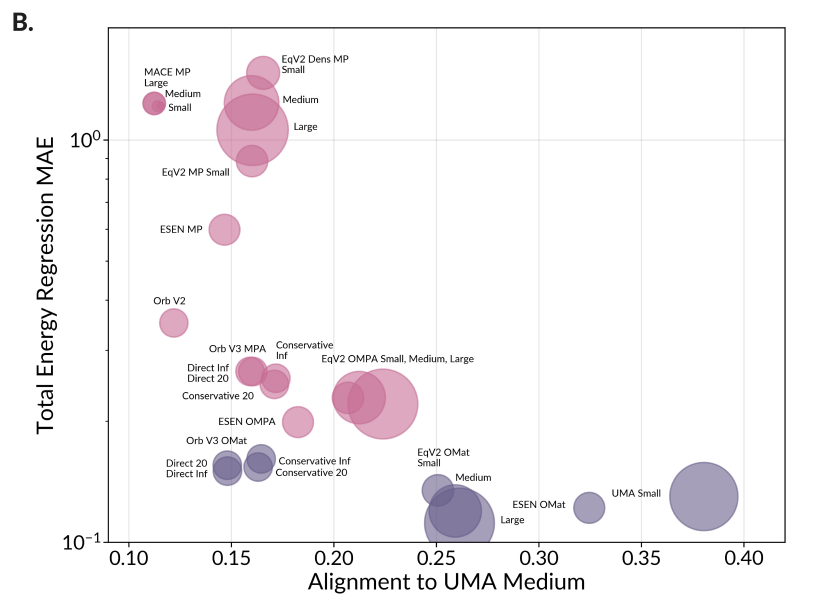

The better a model performs on its training task, the closer its representation gets to that of the best-performing model. The researchers say this suggests high-performing models learn a shared representation of physical reality. The complexity of internal representations also falls within a similarly narrow range across all models, pointing to a universal structure.

Novel structures expose generalization limits

The analysis also shows clear limitations. For known structures similar to training data, strong models produce matching representations, while weaker models develop their own, less transferable solutions. But for completely novel structures that differ significantly from training data, almost all models fail. Their representations become shallow and lose important chemical information.

Current materials models haven't reached foundation model status yet, the researchers argue, because their representations are too heavily shaped by limited training data. True generality requires far more diverse datasets. The team proposes representation alignment as a new benchmark: a model only qualifies as foundational if it shows both high performance and strong alignment with other top-performing models.

This lack of generalization beyond training data is a familiar problem with current AI models. Research shows that transformer architectures, for example, systematically fail at composition tasks—combining known facts into new derived facts—when facing out-of-distribution scenarios.

Back in May 2024, a study from the same institute showed that different AI models converge toward shared representations as performance increases. The researchers called this "Platonic representation," a reference to Plato's Allegory of the Cave. The new study is the first to apply this concept to scientific models, providing evidence that specialized AI systems for chemistry and biology may also converge toward a universal representation of matter.

The recently published SDE benchmark for scientific research shows yet another form of convergence: models often land on the same wrong answers for the hardest questions. Here too, the best models showed the greatest agreement. An earlier study found the same pattern in the context of AI systems supervising other AI processes - this similarity in assessments creates blind spots and new failure modes.

AI News Without the Hype – Curated by Humans

As a THE DECODER subscriber, you get ad-free reading, our weekly AI newsletter, the exclusive "AI Radar" Frontier Report 6× per year, access to comments, and our complete archive.

Subscribe nowAI news without the hype

Curated by humans.

- Over 20 percent launch discount.

- Read without distractions – no Google ads.

- Access to comments and community discussions.

- Weekly AI newsletter.

- 6 times a year: “AI Radar” – deep dives on key AI topics.

- Up to 25 % off on KI Pro online events.

- Access to our full ten-year archive.

- Get the latest AI news from The Decoder.