ChatGPT might be draining your brain, MIT warns - what ‘cognitive debt’ means for you

A new MIT study suggests that using AI writing assistants like ChatGPT can lead to what researchers call "cognitive debt" - a state where outsourcing mental effort weakens learning and critical thinking. The findings raise important questions about how large language models (LLMs) shape our brains and writing skills, especially in education.

Researchers at the MIT Media Lab looked at the cognitive costs of using LLMs like ChatGPT in everyday writing tasks. Their 200-page report, "Your Brain on ChatGPT," focused on how AI tools affect brain activity, essay quality, and learning behavior, compared to traditional search engines or writing unaided. At the heart of their results is the idea of "cognitive debt": when relying on AI makes it harder to build and maintain your own thinking skills.

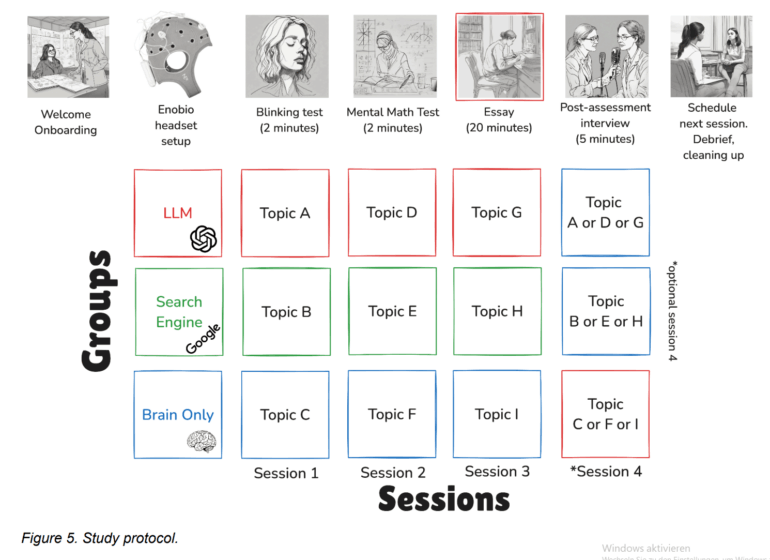

The experiment divided 54 mostly college students from five Boston-area universities into three groups: one used OpenAI's GPT-4o (LLM group), another used traditional search engines (but no AI-generated answers), and a third wrote essays without any outside help (brain-only group).

Image: Kosmyna et al.Over four months, participants completed three essay-writing sessions, each tackling a real SAT prompt within 20 minutes. In an optional fourth round, 18 students switched conditions: those who had used the LLM now wrote without it (LLM-to-brain), while brain-only students tried the LLM for the first time (brain-to-LLM), both on topics they had already seen. The study used EEG to track brain activity, NLP analysis to examine essays, interviews, and both human teacher and AI grading.

Weaker brain connectivity points to outsourcing of thought

EEG data revealed clear differences in brain connectivity across the groups. The brain-only group showed the strongest and most widespread neural networks, suggesting deep internal processing, focused attention, and heavy use of working memory and executive control. In other words, writing without any tools forced students to engage more parts of their brains at once.

The search group showed a moderate level of engagement, reflecting the work of processing and integrating external information, but with more top-down control than the LLM group.

The LLM group had the weakest neural coupling, pointing to a more automated, procedural integration and overall less mental effort. Essentially, with AI, the brain worked less deeply and handed off more of the cognitive load to the tool. Connectivity in this group even dropped over the first three sessions, which the researchers interpret as a kind of neural efficiency adjustment.

The fourth session was especially revealing. Students who switched from LLM to unaided writing showed weaker neural connectivity and lower engagement of alpha and beta networks than the brain-only group. Their activity was higher than brain-only students in their first session, but still failed to reach the robust levels of seasoned brain-only writers. Previous reliance on AI may blunt the ability to fully activate internal cognitive networks.

By contrast, those using the LLM for the first time (brain-to-LLM) showed a spike in connectivity across all frequency bands, suggesting that integrating AI output with their own ideas required extra mental work. The team sees this as the effort of aligning external AI suggestions with an internal plan for the essay.

Homogenized writing and poor recall

NLP analysis found that the LLM group produced more homogeneous essays, with less variation and a tendency to use specific phrasing (such as third-person address), and included the most named entities. The search group sometimes showed patterns reflecting search engine optimization (like frequent use of "homeless person" in philanthropy essays), and used fewer named entities than the LLM group, but more than the brain-only group.

One of the sharpest differences came in post-session interviews. After the first session, over 80% of LLM users struggled to accurately recall a quote from their just-written essay - none managed it perfectly. The search and brain-only groups did much better. This pattern held in the fourth session: the LLM-to-brain group again had major deficits in recall, while the other groups performed significantly better. The researchers see this as a core symptom of "cognitive debt": early dependence on AI leads to shallow encoding, and poor recall suggests that essays created with LLMs are not deeply internalized.

In contrast, the brain-only group showed stronger memory, backed by more robust EEG connectivity. The researchers argue that unaided effort helps lay down lasting memory traces, making it easier to reactivate knowledge later, even when LLMs are introduced.

Human graders also described many LLM essays as generic and "soulless," with standard ideas and repetitive language. The study notes that the brain-to-LLM group may have shown more metacognitive engagement: these students, having written unaided before, may have mentally compared their own earlier efforts to the AI's suggestions - a kind of self-reflection and deeper processing tied to executive control and semantic integration, as reflected in their EEG profiles.

LLM group sticks closer to familiar ideas

The researchers are especially wary of one preliminary finding: LLM-to-brain students repeatedly focused on a narrower set of ideas, as shown by N-gram analysis and interview responses. This repetition suggests that many did not engage deeply with the topics or critically assess the material provided by the LLM.

According to the study, if people don't think critically, their writing becomes shallow and biased: Repeated reliance on tools like LLMs replaces the demanding mental processes needed for independent thought. In the short term, cognitive debt makes writing easier; in the long run, it may reduce critical thinking, increase susceptibility to manipulation, and limit creativity. Simply reproducing AI suggestions, without checking their accuracy or relevance, means giving up ownership of one's ideas - and risks internalizing superficial or biased perspectives.

Study limitations

While the findings shed important light on "cognitive debt," the authors note several limitations. First, the sample size was small: 54 participants, with only 18 in the fourth (crossover) session. Larger samples are needed for stronger conclusions.

Second, only ChatGPT was used as the LLM. The results can't be generalized to other models, which may have different architectures or training data. Future studies should try multiple LLMs or let users pick their preferred tool. The study also only addressed text-based tasks; adding audio or other modalities could open up new questions.

Another limitation: the essay task was not split into subtasks like brainstorming, drafting, and revision, which might allow for more detailed analysis of different phases. The EEG analysis focused on connectivity patterns, not power changes, and the spatial resolution of EEG limits precise localization of deeper brain activity, so fMRI could be a logical next step. Finally, the results are context-dependent and focus on essay writing in an educational setting.

The paper has not yet been peer-reviewed.

Implications for Practice

The key takeaway is that heavy, uncritical use of LLMs can change how our brains process information, potentially leading to unintended consequences.

For educators, this underscores the importance of thoughtful integration of LLMs in the classroom - especially since students are likely to use these tools anyway. Early or excessive dependence on AI could hinder the development of critical thinking and the deep encoding of information.

The results also suggest that solo work is crucial for building strong cognitive skills. The comparison with the search group is telling: even with tools, the act of searching and integrating information is more cognitively demanding and beneficial than simply accepting AI-generated text.

In practice, this could mean using LLMs as support tools later in the learning process, after students have developed a solid foundation through unaided work - an approach supported by the positive neural response seen in brain-to-LLM students. However, it's unclear what would happen if students continued to use LLMs exclusively from that point on.

It's also important to consider the specifics of the experiment. The strict 20-minute time limit meant that using an external tool cost valuable time, giving the brain-only group more room for thinking and writing. In real-world scenarios with looser deadlines, the effects of "cognitive debt" could look different - especially if students are given reasons not to simply generate a finished text.

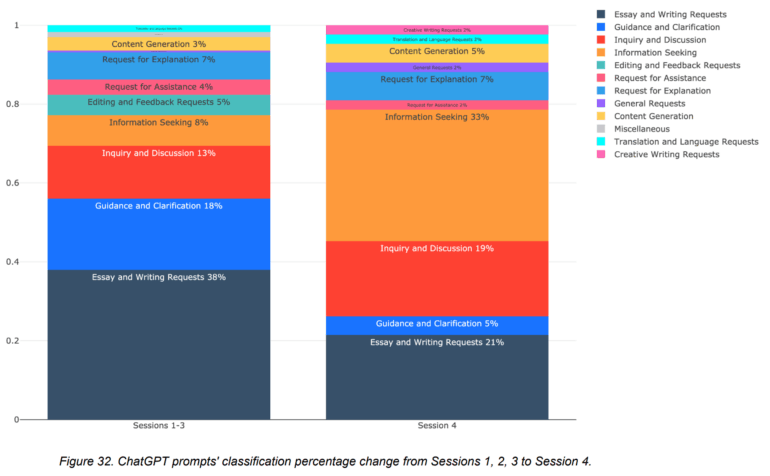

Motivations for topic choice also varied by group. In session two, the LLM group picked topics based on personal engagement. The search group weighed engagement against familiarity. The brain-only group instead clearly prioritized prior experience ("similar to a previous essay," "worked on a project with that topic"), likely because they knew they wouldn't have outside resources. These different approaches could have practical implications for how students tackle assignments when certain tools are available - or not. The decision to use only familiar topics in session four also matters. While this made it easier to compare writing, it's unclear how students would have adapted if forced to switch tools while writing about something entirely new.

The study also doesn't fully explore how different types of LLM use affect outcomes. While it details how students used ChatGPT - for generating, structuring, researching, or correcting text - it doesn't say how these modes influenced brain activity, recall, or sense of ownership.

It's still unclear whether reflective, assistive use of LLMs would have different effects from mostly passive copying of AI-generated text. Future teaching strategies should consider not just tool use in general, but how students interact with LLMs - companies like Anthropic, for example, now offer their chatbot with a dedicated learning mode.

The bottom line: it's still a good idea to use your own brain. How much, exactly, remains an open question.

AI News Without the Hype – Curated by Humans

As a THE DECODER subscriber, you get ad-free reading, our weekly AI newsletter, the exclusive "AI Radar" Frontier Report 6× per year, access to comments, and our complete archive.

Subscribe nowAI news without the hype

Curated by humans.

- Over 20 percent launch discount.

- Read without distractions – no Google ads.

- Access to comments and community discussions.

- Weekly AI newsletter.

- 6 times a year: “AI Radar” – deep dives on key AI topics.

- Up to 25 % off on KI Pro online events.

- Access to our full ten-year archive.

- Get the latest AI news from The Decoder.